Be there God or none, be there gods or one—this man is my god. “” Hadrian, Act 3

one must have a rare recipe for perfection on the operatic stage to deny, without exception, that this opera was a success. and we must congratulate this bold project undertaken by alexander neef and executed by rufus wainwright and his entourage of canadian artists bringing their proven talents to this new and soon-to-be tested work. it was a success, but a hitchless opening night on schedule is not high enough of a bar to chuck the ballasts of doubt that have weighed upon this production since its inception.

Hadrian will succeed first and foremost because it showed up – “”robert harris, theWholenote

wainwright wanted to create a grand opera, and this was exactly that—so let’s take stock: five near-nude dancers (gyrating onstage for almost the whole length of the opera); a gargantuan bust of a greek god (Antinous eventually became a god); larger than life projections (turns out that bust was an image on a screen, replaced by a trite nebulous backdrop); there’s fat shaming; there’s a well-behaved dog onstage (some kind of greyhound mix); a marathonian lengthiness (160 minutes long, with almost no pause for applause); oh, and there’s the COC’s orchestra at full gale force conducted brilliantly by maestro debus.

[Hadrian] can only fail if they haven’t pushed their vision far enough, haven’t solved the knotty and intractable artistic problems that bedevil every creative work, or, faced with the horrors of rewrite after rewrite, have taken the easy way out. It can fail if it is just another pop pastiche, floating along on the grandeur of operatic convention, ear and eye candy for a new generation of operagoers. “” robert harris, theWholenote

(the libretto)———this was daniel macivor’s first libretto and his first major interaction with the artform, one achieved through a recommendation by COC regular atom egoyan, and overseen by neef—and it shows that it was his first. the libretto was at times perfunctory and wainwright’s orchestration was not always enough of a lubricant to push the bulk of the story through the many winding turns of its dreamscape. its best moments were its simplest, wherein the words were quiet enough for the music, and the talents of the singers to shine. it’s asides towards a modern audience did not always land well, for example thomas hampson speak-singing ‘Leave me alone’ over a quiet orchestra was one such mishap. then there was the ‘Men only speak to hear themselves’—although very true and a welcome woke-ism, was not couched in enough quick-wittedness elsewhere to come off as natural.

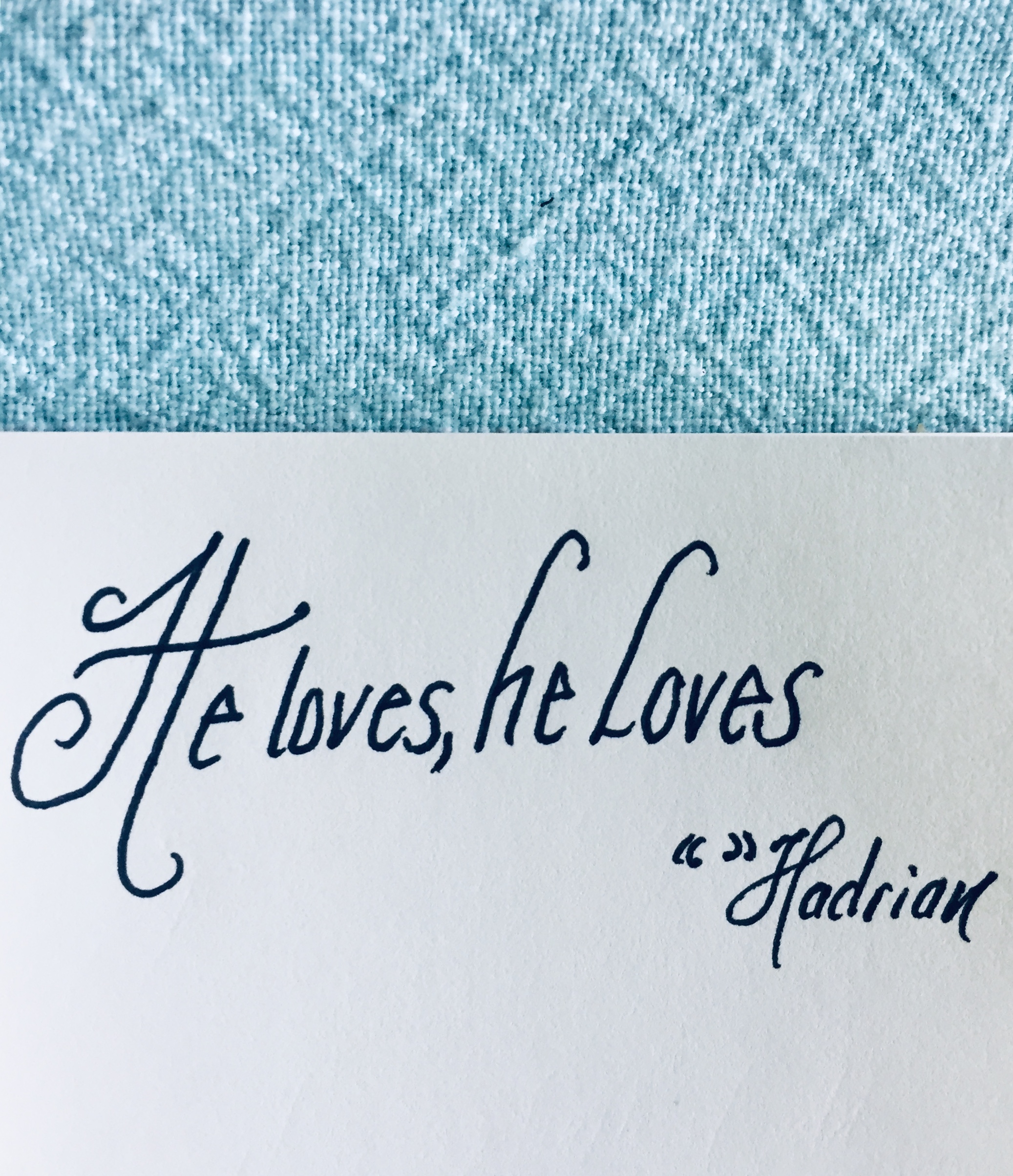

nevertheless, those aforementioned shining moments is as much thanks to the libretto as to the performances. the repetitive “He loves, he loves..” in the middle of the fourth act when Sabina realizes that her husband’s love for Antinous is genuine, was sung with hair-raising feeling by ambur braid. that was my favourite part of the night; it was one of the few musical landmarks in the production. i was sweating through my shirt—her soprano ascended like a white obelisk amidst the huddle of tenors and baritones!

For once, even though they are seeing a piece set in ancient Rome, COC audiences will not have to trade the omnicultural carnival of the Osgoode Subway Station for the hermetic confines of the Four Seasons Centre when they go to the opera. For once, the two worlds will travel in synchronicity, both alive to the terrors and dangers, joys and exuberance, of actual lived life. “”robert harris, theWholenote

whereas the set design achieved it’s intimations of an ancient dreamscape and the orchestration, by definition, was classical—whatever relevance to our modernity this opera achieves can be attributed almost entirely to the libretto:

(ben heppner)———he stole the show—for 10 minutes. it was absolutely brilliant to see him back on the COC stage (in a pinched role as Dinarchus). his unique voice is unmistakable, i had almost forgotten his role when he began singing. there’s a lilt to his tenor that impresses not by force but by a cajoling intimacy. perhaps i’m still thinking of his magnificent final performance before retirement in the title role as Peter Grimes five years ago. in fact i anticipate a field day finding similarities between Hadrian and Grimes—and, despite thomas hampson’s towering performance, that role might have been better suited for a tenor. at any rate i was clam-happy so see heppner out of retirement (someone should update his wikipedia).

(tiny dancers)———not that it needed any, but the five dancers were the saving grace of the production. for a libretto that had to juggle forbidden love and the intrigues of the late roman empire, the celebration of homoerotic love might have been too much on its plate—especially for a period piece. that task, as well as the celebration of hellenic humanism, was gorgeously choreographed through the dance numbers. the presence of the dancers all throughout—and their supple marathonian stalwart fitness—was a constant source of movement and depth to the storyline.

perhaps you can’t quite call it grand opera if there’s no dancing, but the choreography served a meaningful and independent role. although the use of dancers was a bit liberal, they were the one consistent feature throughout the many changing scenes. and their placement throughout was a deviation from form; the ballet pieces in a grand opera are usually reserved for the beginning of the second act—wagner’s Tannhäuser was pulled just after the third performance for placing the dancers in the first act. but i don’t imagine anyone would complain too loud about overuse of those dancers…

(convoluted finale)———whatever the much reported creative scuffles between wainwright and macivor throughout the last three years, they are insignificant compared to the evident internal struggle on just how this opera should end. which is also a struggle over what is to be the centrepiece and mission of story—is it one about a man mourning love lost, or an emperor losing control of his court?

for about ninety percent of its length it was about a man and his love. and whatever praise it enjoys is thanks to that. ‘This man is my god’ achieved a profundity that it abandoned in the last ten minutes. instead it tossed the rope to a story about an empire lamenting the end of polytheism. thankfully, the music stayed for the challenge and the orchestra made up for the emotional intimacy the finale lacked, an intimacy that would have been a boon for the production’s relevance to our 2018 audience.

nevertheless; nevertheless—nevertheless this was a success of an opera. if indeed you do have that aforementioned recipe for operatic perfection, keep in mind the current conditions within which it must be prepared. we are in need of generating a new generation of opera goers. and we must do so from a population whose high bar for stimulation has been cultured by the intimate personal point-of-views readily available on netflix. a night at the opera should be grand and exciting, even if some subtleties of form are left behind, even if it is a ‘grand opera for grand opera’s sake’. these are exciting times at the COC, and wainwright’s Hadrian is exactly the man for the hour.