From the strange opening notes there was murmuring, which escalated to shouts as the ballet began. Soon the audience had descended to a donnybrook complete with fisticuffs between pros and antis—Maurice Ravel in the middle of the fray crying “Genius! Genius!” It is hard to say whether the outrage was provoked more by the music or the dance, though before long the uproar had overwhelmed the music. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

there’s nothing quite like stravinsky’s Rites—and not much use differentiating between the music or the dance. i think that to be the characteristic trait of the cathartic element in music: it’s ability to tranquilize the more critical tendencies of the human mind, to intoxicate, entrance and elevate consciousness to the height of a feverish dream-logic, a bottomless imaginarium no image or ‘plastic art’ could encapsulate. to dance in such a barbarous state provokes either ecstatic devotion or unreserved disgust—nothing in between. and that is the state of pina bausch’s dancers in the production below…

Music here was a terrible narcosis, a sort of intoxication and oblivion, a going off into irrational planes. Drunken mysticism, ecstatic sensations against a background of profound pessimism permeating existence. It was not form or harmoniousness or Apollonic vision that was demanded of music, but passion, feeling, languor, heartache. Such was Tchaikovsky’s music and such also what the music of Rachmaninoff developed into. “” leonid sabaneyeff, Sabaneyeff

Rites of Spring is the most potent assault and antagonism of form and harmoniousness in this catalog of composers. ‘drunken mysticism’—is that not what i anticipated least of the classical repertoire? ‘irrational planes’? and ‘profound pessimism’?—i couldn’t ever talk myself out of believing those were the only kind of music that mattered…

(program)———

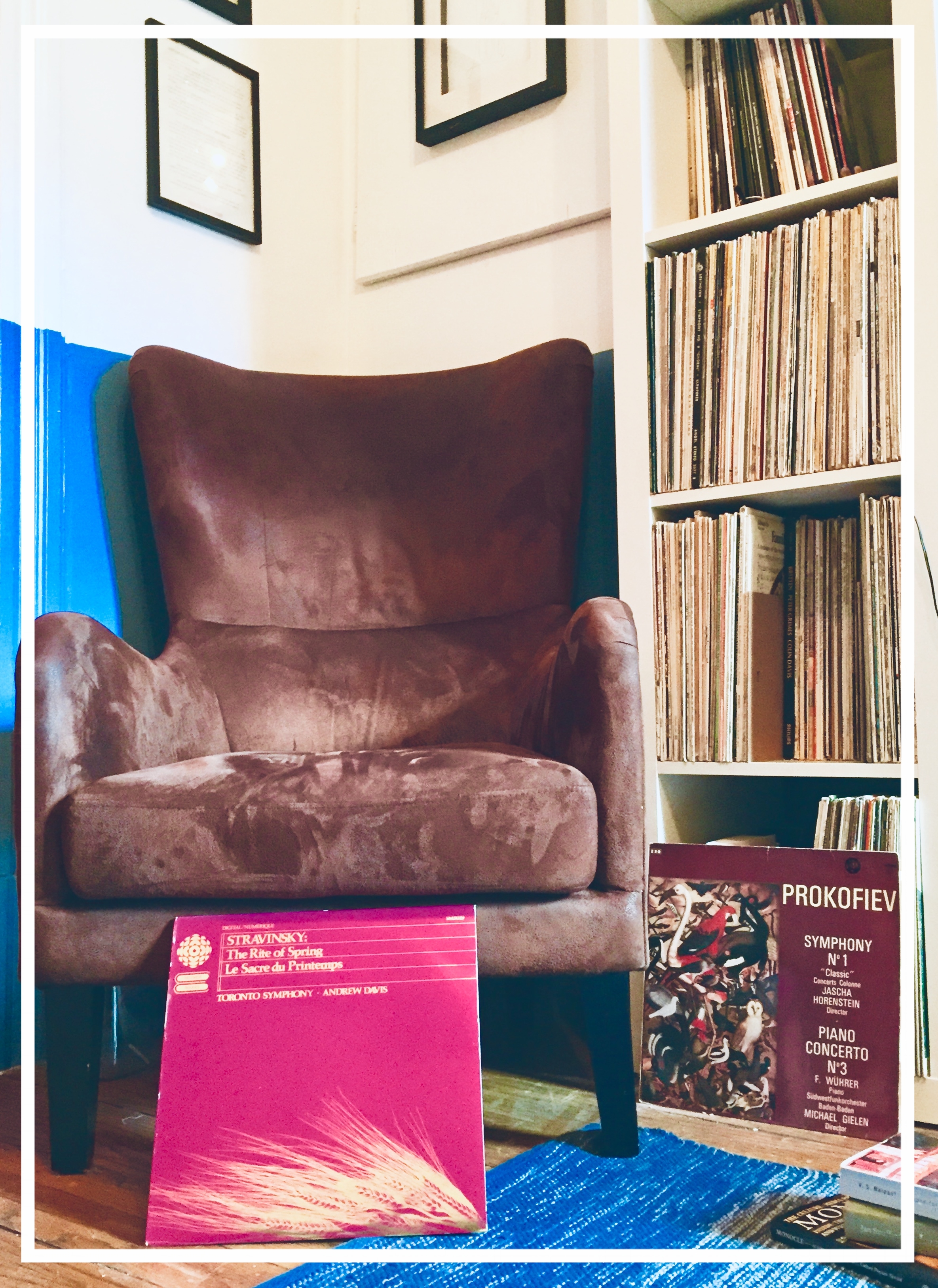

CBC Enterprises Recording. Printed in Canada // Igor Stravinsky (June 1882-April 1971) // Le Sacre du Printemps (1913) //

Toronto Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Davis

Part 1: - Introduction

Augurs of Spring, Dance of the Adolescents

Game of the Abduction

Spring Rounds

Games fo the Rival Cities

Entrance of the Celebrant

Adoration of the Earth

Dance to the Earth

Part 2: - Introduction

Mysterious Circles of the Adolescents

Glorification of the Chosen One

Evocation of the Ancestors

Ritual of the Ancestors

Ritual Dance of the Chosen One

(Bon Iver’s anti-lyricism)———

To put it another way, Stravinsky reversed the traditional relationship of content to form. In the past form was central, the content subordinate. The main point of a work was the whole. In Stravinsky and much music following him, the power of the ideas is the central issue; the form is looser, there to serve the content. [...] He died in New York in April 1971. For his resting place he wanted to return to the triumphs and excitement of his youth: at his request he was buried in Venice beside Diaghilev. I still have a newspaper headlining his death. Like many musicians I felt the loss personally. All of us wondered when somebody would step up to fill his shoes. To date, I think, no one quite has. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

content over form; whole over parts—these appear to me as fundamentally anti-classical instincts; instincts which, incidentally, form the majority of the musical experiences that have shaped my musical education: or how else could one describe, conceive, the landscape depicted in Bon Iver’s discography as anything other than a rebellion against forms, partitions, lyric, song (most of Bon Iver, Bon Iver is a long uninterrupted ‘song’). yet their musical landscape isn’t formless, or free from dissonant fragments (especially not). instead, it’s characteristic trait is also what makes catharsis in music possible: the instruction of form by content, parts by the whole—lyric by music. music of that sort liberates its audience from the competition for attention between lyrics and music; those aforementioned critical tendencies are first submerged by music and therein contours of this subterranean state of mind are refined by words. this is the power of music over lyrics. the power experienced as catharsis. the power personified moreso by Bon Iver than anyone else in folk music. --and perhaps the same can be said of stravinsky in the classical repertoire.

(a sophisticated primitivism)———

‘Contes Barbares” Paul Gauguin—1902—Oil on canvas

has there been a more convoluted misapprehension of historicism, or decidedly antagonistic attitude towards the relationship between words and their meaning, than the concept of a ‘sophisticated primitivism...

At this point Paris was at the center of a revolutionary fervor in the arts, some of which involved a sophisticated primitivism. [...] From the eerie bassoon wail that begins it, the piece is a revolution in sound and in its very conception, but a revolution founded on a return to the primeval. Winds twine like vines, strings pound like percussion, French horns howl like elk in heat. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

what is most compelling of Rites? is it not that it seems incapable of sophistication? incapable of every equivocal, triquivocal (quinquivocal…) systems of communication that civilized art cannot do without. Take for example paul gauguin’s painting Contes Barbares (Barbarian Tales)---the two women sitting in the foreground, their gazes aimless and serene, poses relaxed and athletic, enveloped in a scenery of cloistral greenery. in contrast to this primitivism, perhaps under the category of ‘sophisticated’, is a man cloaked in blue, with orange hair and green eyes staring rather aggressively at the viewer. it’s a painting that belongs neither to primitivism nor sophisticated civility--lingering in an eerie hyphenation of both.

Rites it’s music for the human animal, that being to which thinking happens to. how is possible to respond to music of that sort without equivocal gestures? what are the mimetic gestures of a musical idea that can be described as a ‘sophisticated primitivism’?—of the many possibly brilliant answers, pina bausch’s choreography remains the definitive one, par excellence:

(pina)———

The choreography was by Nijinsky, who was equally determined to revolutionize his art. [...] Nijinksy’s choreography is virtually antiballet, the dancers’ movements hunched, ungainly, spasmodic, but with a strange beauty. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

there’s this unmistakable quality of a genuine ecstatic possession in bausch’s choreography. its ‘strange beauty’. the singularity of their mental-state is refracted into a dissonance of gestures, slaps, sulks, leaps, contortions, yelps and gasps. the creative freedom to express this multivariety of dissonance requires a dominating musical spirit as a contrasting source of consonance. the brilliance of an experience like bausch’s choreography is at its highest potency when under the hypnosis of the strong intoxicating dionysian element in music, which becomes the source of cohesion and consonance in relation to other artforms.

Stravinsky began on a high plane with Firebird, topped it with Petrushka, and in 1913 topped it again with one of the most astonishing feats of musical imagination in history: Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring). Again the basic story of the ballet was Stravinsky’s. In a primeval Russian village we watch the various rites and dances of spring. At the end a virgin is chosen for a sacrifice: she must dance herself to death. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

not that she is chosen for sacrifice but that she must dance herself to death is the bridge between the choreography and the music. a ‘terrible narcosis’ ‘dionysian madness’ is the presupposition of Rites, it’s ‘content’. it is this wrestle between control and oblivion that gives this ballet its form—it is a triumph of a creative mission that the end of the composition (and choreography) ends in oblivion.