I believe that of the leading twentieth-century Russian composers, Prokofiev is the finer artist of the two—his technique, his judgement, his range, outstrip Shostakovich. But I also believe that Shostakovich is the more important of the two. More than his colleague, Shostakovich witnessed the cataclysm of midcentury Russia before his eyes, felt it and lived it. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

this symphony in five words?—warring strings and militant percussions. the last time i listened to this recording, in late july, the temperature was stuck in the high twenties (and threatened low thirties)—no time at all for the fury and delirium of this tenth symphony’s Allegro. it’s as if the protracted length of the first movement was a design to lull the attention with the mirage of a scenery just shy of pastoral; only to arrive, at the end of that long and steady road, at the jagged shoulder of a wicked cliff— it’s a short fall, just above four minutes long, but the flailing delirium is not alleviated until well after the conductor’s baton has been tucked safely back into its holster.

i made plans back in july to come back to this symphony in second or third week of november, and even now i still feel it too early, still too warm for this symphony. december is a month wholly for russian composers of the previous centuries. not for the sake of any wool-slipper coziness, but of the pitiless gaze of their proximity to the iciest winters. and perhaps if you had to suffer stalin as a cultural and political one-man-legislature, winter is more than season… it is the ice-wall of oppression against which music must be charged like a bayonet, like an icepick—

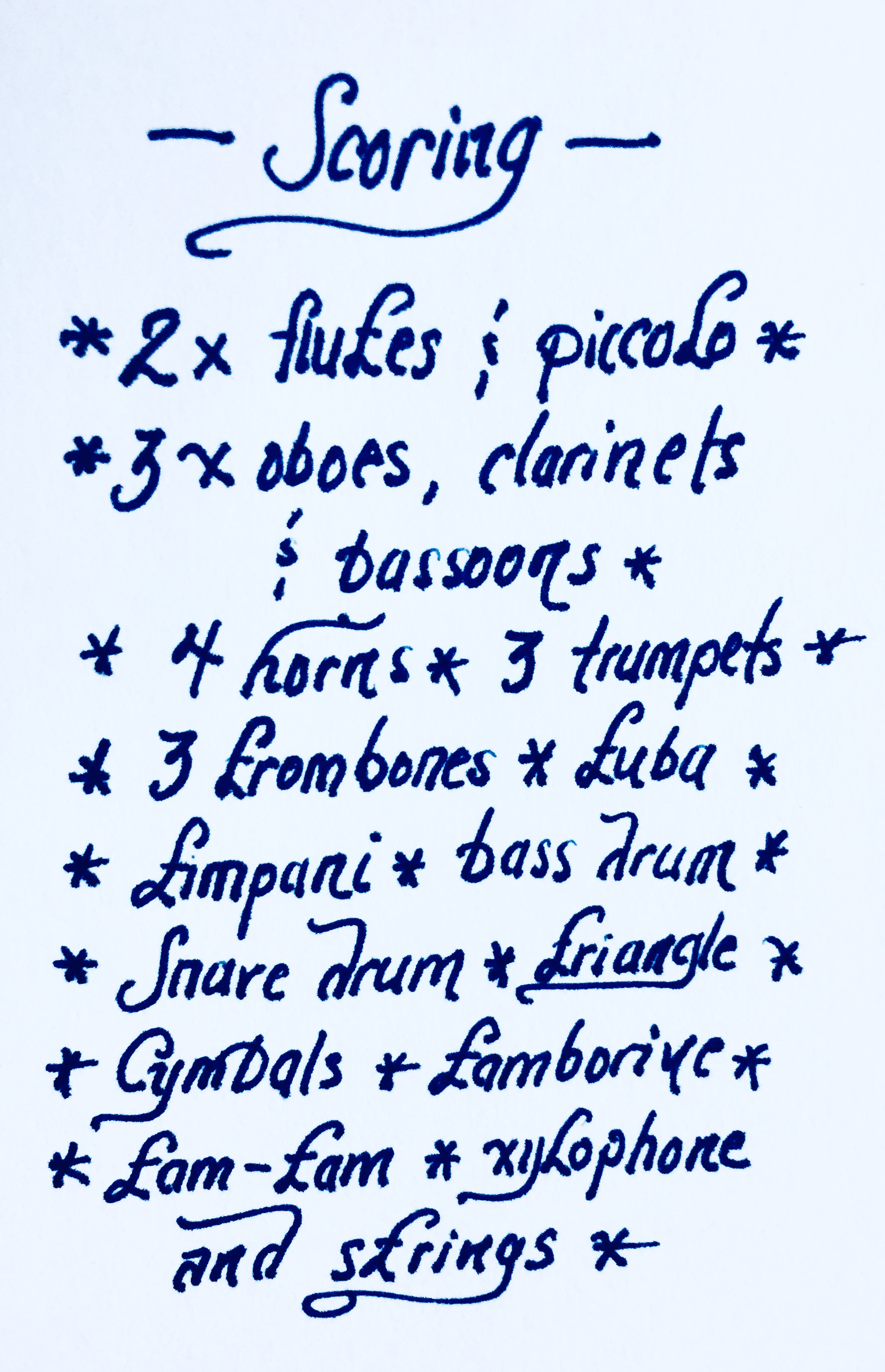

(program)———

Deutsche Grammophon Recording. Printed in West Germany // Dimitri Schostakowitsch (1906-1975) // Symphony no. 10 in E minor, op.93

Berliner Philharmoniker, Conducted by Herbert Von Karajan

Symphony no. 10

Moderato (moderate)

Allegro (quick, lively)

Allegretto (quick, slower than allegretto)

Andante — Andante (slow, faster than adagio)

Here is where the ambiguity of instrumental music comes into play, and the game that artists of any integrity must engage in under a totalitarian regime. Are those climaxes a matter of stern heroism, as Stalin would wish them to be, or transports of anguish and rage? “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

(seriousness in regards to music)———

He had been something of a brash young man, a provocateur, but in 1936 after an outraged Stalin walked out on a performance of his rowdy opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, a newspaper article declared that if he kept on this path “things could end very badly.” [...] Shortly after that, Stalin sent him to America on a tour. Shostakovich knew, and Stalin knew he knew, that artists returning from these tours often found themselves shot. It was maybe a little joke on Stalin’s part, to give the doomed a vacation first. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

i can’t think of anyone since the Dixie Chicks whose music has been enough of a threat to an administration to warrant any serious kind of trouble—and though being told to shut up and sing is no invitation to creative freedom, it’s still in no proximity to the suffocating stringencies imposed upon dissident composers by dictators of the previous century (and of the current: vladmir putin v. Pussy Riot)—

Stalin, you see, was highly involved in the arts and convinced of their importance to society. That’s why he murdered so many artists he considered bad influences, and/or he just didn’t like their stuff. In general, when politicians get interested in the arts, artists better run. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

michelle obama was recently on the leading feel-tank for the democratic party: stephen colbert’s Late Show. she was promoting her new book ‘Becoming’, which, at first glance, would benefit tremendously from being judged by its cover—that combination of white, mint and black is the perfect abbreviation of the calculating intellectualism thinly veiled by a kind of chic charisma aesthetic of her husband’s talk-show appearances. her performance alongside colbert was magnificent. hers was the style i’d like to describe as a waterbrand (as opposed to a firebrand)—it’s the same intensity, mixed with a bankable knack for understatement. her tremulous barack-esq shout-whispers were as usual irresistible—especially since it's been so long since we’ve been tucked into bed tenderly by an american president (2 years and counting). but amidst all the stage-worthy cadences and dramatized pauses, she said something almost off the cuff that knocked the wind out of me, and was a reminder of what a miraculous gift that first family was to the PR department of american culture for eight years. it came during her explanation of her decision, in the first year of her husband’s presidency, to persist with a scheduled halloween white-house party despite the concerns of her advisors regarding the contrast between such festivities and the dire economic crisis gripping the rest of the nation. michelle is, on the whole, more quick-witted than barack, which is evident as she summed up her response with: ‘It’s halloween dudes, c’mon [...] the country needs seriousness—but they need joy at the same time.’

in regards to the musical experience in general, i can’t do without those two things: seriousness and joy. and perhaps i could make a case that one is impossible without the other: i have very little sympathy for that morose kind of seriousness, the kind mollified only by sighs and grimaces—and just as little for that nervous cheerfulness that is, ultimately, an evasion.

perhaps i’ve taken too long an arc to get to this point: that our music lacks, in almost every instance, seriousness. they are in an ever-shrinking minority, those musicians who are still imbued with the stark and vibrant colours that belie the spirituality of their art. do we still make music serious enough to make tyrants feels uncomfortable? uncomfortable because of the proximity of it’s howls of anger to the sighs of joy they can no longer tolerate?

no one has been more successful in the last century in exercising the imagination of the reading public in regards to the more unsettling details in the tendencies of a surveillance state, than george orwell. but a less than popular author of the same era is by far the more interesting psychologist in regards to the morale of the citizenry subject to tyrannical surveillance—and that is of course, aldous huxley. in fact a now famous comparison between huxley and orwell, made by neil postman in his book ‘Amusing Ourselves to Death’ is especially pertinent to our topic here:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism.

Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumble puppy. “” neil postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death

the same cautionary could be applied to music-making: what reason is there to ban a musician, if no one listened to her music with any seriousness? (and if i, in the meantime, struggle to define what i mean by ‘seriousness’ i’ll settle to articulate it as the opposite of passivity, trivial orgy porgies). the shooting of a single shostakovich upon his return from america is nothing compared to stalin’s unattainable fantasy of an audience who has cultivated a passivity to the urgently volatile ideations in his music. that fantasy in the kind of anhedonia of our current musical landscape, and the quality of our musical education. an anhedonia generated by our inability to navigate our ‘almost infinite appetite for distractions’...

classical music—instrumental music in general—is so far the best accomplice i could find for the navigation of a path towards serious in regards to music. which is as well a path towards joy—yet another probable translation of what our dear Nietzsche could have meant when he said: ‘what i really want from music is that be cheerful and profound, like an afternoon in October.’ profundity and seriousness, joy and cheerfulness—part and parcel of the classical repertoire…

there is as well a tremendous capacity for ambiguity in instrumental music that is precisely it most interesting feature: it’s both here and there; you can hear it for the hundredth time and yet your cleverness never runs out of stunts, out new meanings to throw unto the music, like a lampshade:

Music is as immediate an objectification and copy of the whole will as the world itself is, indeed as the Ideas are, the multiplied phenomenon of which constitutes the world of individual things. Therefore music is by no means like the other arts, namely a copy of the Ideas, but a copy of the will itself, the objectivity of which are the Ideas. For this reason the effect of music is so very much more powerful and penetrating than is that of the other arts, for these others speak only of the shadow, but music of the essence. [...] We must attribute to music a far more serious and profound significance that refers to the innermost being of the world and of our own self. “” arthur schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation

(simón bolívar youth orchestra)———i was altogether disappointed by simón bolívar youth orchestra’s performance of this symphony—conducted by the always seemingly possessed gustavo dudamel (who has, perhaps second to pianist khatia buniatishvilli, h the liveliest instagram account in classical music). all the urgency (read: energy) of the piece is sucked out the front door. perhaps one would take more into consideration the fact that is a youth orchestra if it wasn’t for having seen other instances of their athletic flare and raucous string sections. i have in mind the first performance of theirs that i saw on that same stephen colbert’s Late Show (in its early days before it began clamouring for ratings). their performance of a rendition of maria teresa’s Fuga Con Pajarillo was absolutely magnificent. even moreso in the performance below wherein the soloist interjects with cadenzas that incorporate local venezuelan musicality.

unless, amid the mystic tones of reawakened tragic music, the gate should open for them suddenly of its own accord, from an entirely different side, quite overlooked in all previous cultural endeavors… “” Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

there’s an invigorating amount of opportunity for the hybrid creations between western classical music and ‘world’ music—the gate is opening wider now than ever for such cultural hybridizations...