In some ways it is an unusual work for a composer more renowned for his wit than for highly charged emotional expression. Yet it is a successful piece, and justifies completely its lasting popularity. “” meirion bowen, notes for the recording

an example of that aforementioned wit is saint-saëns’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (in a minor, op.28) it’s about the craftiest tête-à-tête between piano and violin i’ve ever heard—and one of the most satisfying finales between the two instruments.

Song of the day 04.10.2017/ with one flash of lightning I had thought: this is too belated a beginning, I might never get started. Then another flash, like sabres crashing: is there anyone today newer, earlier, readier than I am——so that I may learn from them? Perhaps I’ve already started...

in remarkable contrast to the previous week, this was for me one of those weeks wherein everything is brilliant and nothing hurt—plus a fair bit of good news. that the last day of the week was also the first of autumn is precisely the kind of timeliness this catalogue celebrates. and in all 52 of these compositions, there is perhaps no other more furiously headlong symphony than camille’s third, which might otherwise pass as a concerto for the organ.

i think the organ is the most pious instrument—both for the historical setting of its use and its characteristic heft and melancholic grogginess. hence the genius on the part of the composer that the title instrument of this symphony is employed almost imperceptibly.

The forces used are of interest, since in addition to the usual orchestral contingent (with triple woodwind groups), the symphony requires an organ throughout, and a piano at which there are two players in the finale only. “” meirion bowen, notes for the recording

(program)———

Deutsche Grammophon. Printed in Germany // Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) // Symphony No.3 in C Minor, Op.78 “Organ” //

Chicago Symphony Orchestra // Conducted by Daniel Barenboim. Gaston Litaize on Organ

1st movement: Allegro moderato (moderately fast)—Presto (very fast)—Maestoso(majestic, stately)—Poco adagio(moderately slow)

2nd movement: Allegro moderato—Presto—Maestoso—Allegro

(our dear Nietzsche)———

Variations of time signature are frequent. Amongst the most remarkable may be cited those of three-one and three-two, which are perfectly inevitable interpolations in the (usually) steady rhythm of 12 and 6 crochets in the bar, and are of considerable importance in urging onwards the feeling of majestic grandeur that leads to the climax of the Finale, where organ and orchestra, in a richly hued wave of sound, attain the very definite attainment of rest at a journey’s end. “” watson lyle, Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art

very little of that grand finale suggests to me, if at all, anything of rest or respite at a journey’s end. there’s too much intent, intensity, too prolonged and suspended a tension for the abbreviated resolution of the finale to be described as ‘rest at a journey’s end’—the high-falutin imaginative interpretations of this watson lyle oft gets ahead of itself, (i’ll be getting back to that shortly).

to describe the sentiment of this finale, i was lucky to recall a word discovered earlier this year. a word that i could almost admit was at the inception of this journal; a word that finds its most accurate definition within the context that Nietzsche employed it, than in its own etymology: saturnalia…

Gratitude pours forth continually, as if the unexpected had just happened—the gratitude of a convalescent—for convalescence was unexpected. “Gay Science”: that signifies the saturnalia of a spirit who has patiently resisted a terrible, long pressure—patiently, severely, coldly, without submitting, but also without hope—and who is now all at once attacked by hope, the hope for health, and the intoxication of convalescence. “” Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

a terrible long pressure: much of this symphony in c-minor could be described as such. thereby the allegro finalizing the 2nd movement is more akin to a saturnalia—that is, rejoicing in strength that is returning, ‘a sudden sense and anticipation of a future, of impending adventures’—than to rest at a journey’s end.

few can appreciate music as much as the convalescing. for them, everything is a hint towards the most excellent health. i’m reminded of one of many bouts of sickliness as a child: it must have been some hideous mix of asthma and bronchitis that left me in a wheezing and prostrated position for two weeks. at the climax of my ailment i was rushed to the hospital where the doctor botched a thigh injection and left me limping for a whole day. the next morning, without any forewarning, i couldn’t have been in better spirits. just like that, i was good health again—sleep has always been the best physician, as such the worst ailments are the ones that leave us sleepless. i remember waking up to a celine dion track playing on my mother’s stereo (A New Day, obviously). i laid awake for a while, dreaming up the plethora of little projects i’ll take on now that i had my health back. when i did finally get up my one leg was still spasmodic, but elation—which is gratitude without a subject—was the only thing i could feel.

more than the desire for rest, or respite, this symphony’s finale taunts the attentive audience to a plethora of projects, big and small, yet to be challenged—

(music as consolation for the pious, as a disciplina voluntatis)———

A time comes when you’re all alone, when you’ve come to the end of everything that can happen to you. It’s the end of the world. Even grief, your own grief, doesn’t answer you anymore, and you have to retrace your steps, to go back among the people, it makes no difference who. You’re not choosy at times like that, because even to weep you have to go back where everything starts all over, back among the people. “” louis-ferdinand céline, Voyage au bout de la Nuit (1932)

after a four month hiatus for the sake of recovery, i’ve returned to reading Nietzsche—continuing where I left off in April with Book Five of his Gay Science. the first topic of the section, in the uncharacteristically critical tone of an essayist, was Nietzsche in top form as a philologist: dragging out from the most improbable, most cavernous nooks, the origin of religious sentiments. moreso the psychological preconditions for the founding of a religion. even with the spirit of rational criticism, there is still much of that Nietzschean spunk and bravado which proves lethal on the topic of religion. nevertheless, whatever he has written that is pertinent to that subject, however scant and convoluted, is also the most penetrating insight available. that is Nietzsche, through and through.

from Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art — Watson Lyle

the introductory sections of Book Five are also very timely in relation to the eight hours of debate i’ve endured, as self-immolation, between jordan peterson and sam harris. the debates (which both parties insisted was every but a debate) was a transatlantic spectacle (vancouver, london and dublin) of peterson’s transcendental capacity for evasion and obfuscation—and harris’ performance-art-display of his incapacity to speak no louder than in the most calm and tranquilized voice of reason (and this is no time for that, of course). peterson fused himself to the corner of the argument wherein god and godliness is an indispensable feature of our civility and harris counter-argued (whilst maintaining a stoic cross-legged ankle-on-knee meditative pose) that everything good that religion infuses into human life can be afforded without all the ghastly superstitions and indefensible sectarianism. the winner at the end of their brief epic, was the ghost of christopher hitchens: sitting just off-stage to remind us how much we would benefit from his self-styled piercingly witty punditry to dismantle the subterranean network of snake-oil salesmanship that peterson passes off as intellectualism—i’ll carve a whole game of tic-tac-toe into my wrists if i ever have to hear him say ‘metaphysical substrate’ again.

what was most annoying about the ordeal was that despite having the overwhelming momentum of truth and reason on his side, harris was altogether ineffectual in wrestling with peterson’s argument that religion was filling a need that was deeper than religion and could not be filled with anything other than religion—that is the sympathetic summary of his convoluted defense of god. harris was too fixated on religion as the most serious problem to articulate his own very valid argument that religion was merely a first attempt, and should be susceptible to the scrutiny that other first attempts are susceptible to (such as astronomy’s astrological origins).

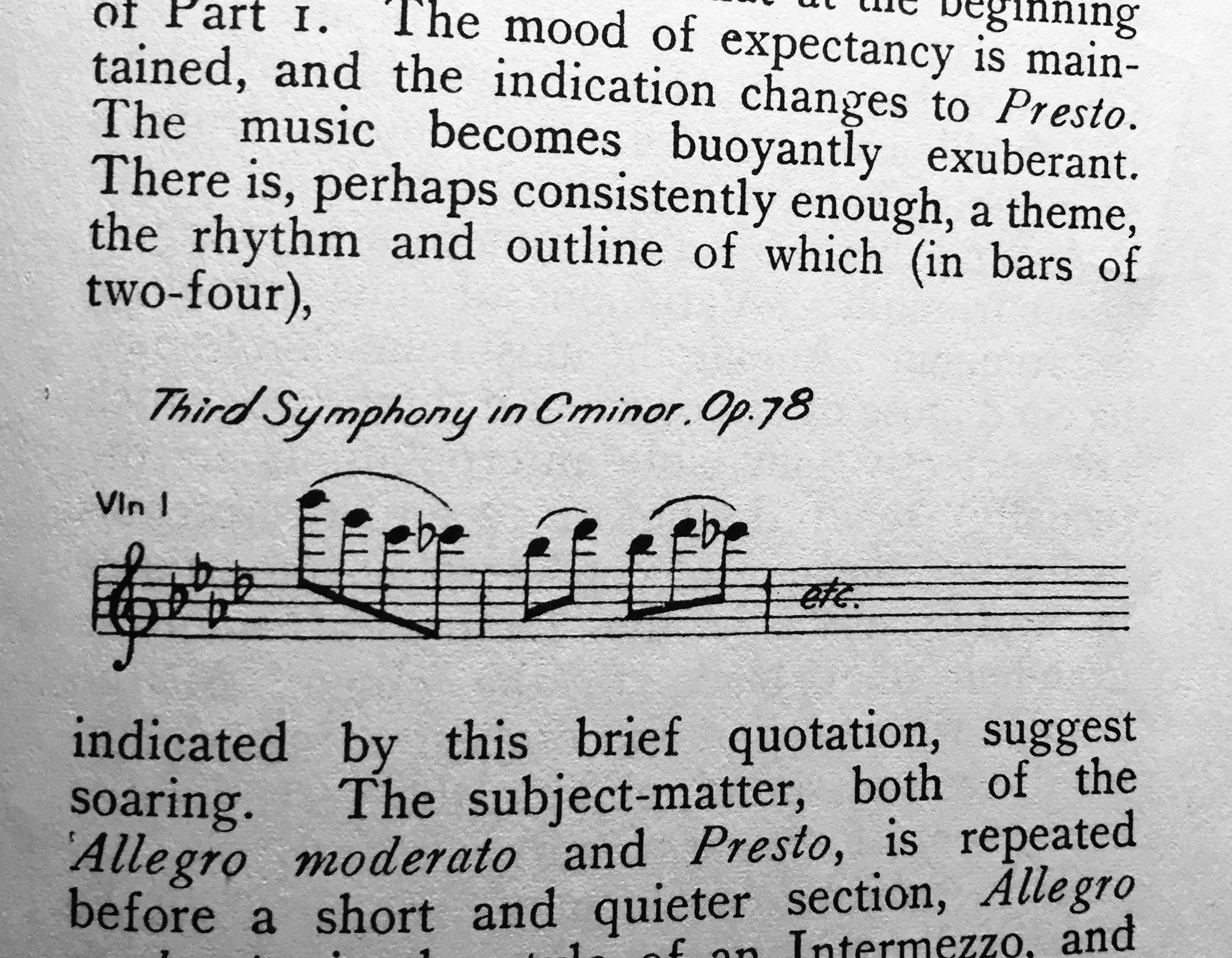

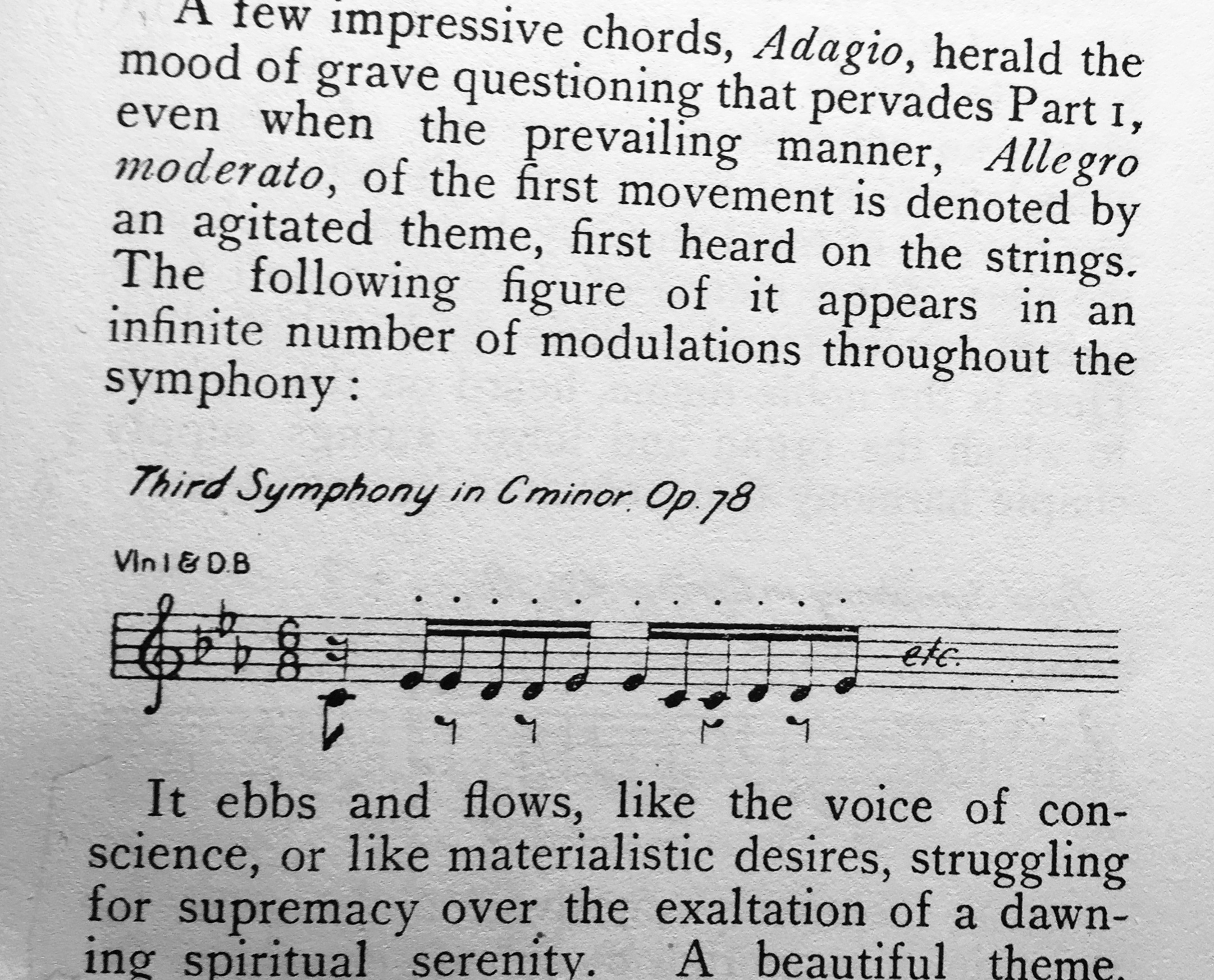

from Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art — Watson Lyle

the word that is lacking in harris’ lexicon—or anyone else forbearing that side of the argument—is: piety. as i described back in my june rant (week38) that piety is a phenomenon that is older—deeper, grainier, more organic, more humane, softer, more transparent, more persistent, harder—than religion. indeed the psychological precondition to the religious type. and in every religion—here i borrow directly from nietzsche—the truly religious, the pious, are almost always the quantitatively insignificant minority. but no mistake should be made in regards to the influence of this minority. each of the approximately 1.5 billion adherents that belong to each of the world religions are oriented in a concentric huddle of belief, at the core of which are those that truly believe in the global project of their religion. this pious core is both the lifesource of the religion’s morale and a threat to the expansion and economization of these beliefs. what we mean by ‘modern religion’ is really a description of how much padding the eccentricities and ruinous urgency that inner core enjoys from its less stringent adherents.

it should follow from all of that, that it is piety—both the characteristics traits and psychological type—that is the ultimate challenge of atheism in our time. and i cannot imagine any cause worthier than that. the superstitions and anti-rational doctrine of religion will always be the penultimate hurdle between us and the global union of our species in celebration of the most cheerful humanism. our atheist too need to be more cheerful, their instincts more subtle, their vitriol toward religion more calibrated, and finally: she must always spare her most convincing argument for the ultimate hurdle. that is, the psychological trait of piety, and the tremendous urgency it has towards the achievement of some sort of new jerusalem, some spontaneous and irrefutable global union.

from Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art — Watson Lyle

christopher hitchens—who has so far been the most successful in the last 60 years at articulating the more embarrassing features of the psychological traits of the religious type—still missed the mark in regards to what is at the core of our need for religion. and it is undeniably a need. with his own infinitesimally subtle and subterranean cleverness, jordan peterson hints at this core. and all of his ‘metaphysical substrates’ are merely dog whistles towards his audience as to why the atheist can’t be taken seriously inasmuch as they are still captivated by the superficial, penultimate hurdles of world religions. and he’s not wrong.

in that same june rant i also described how the religious type make for the most effective atheist inasmuch as they have had such intimate acquaintances from an early age with that intoxicating need for worship, and even moreso for devotion. the children of priests and pastors, especially, provide the most potent insight on the subject. Nietzsche is one such example. in fact i associate his genius to two main sources: his intimate familiarity to religion from early childhood (his father was a strict lutheran pastor), and the utmost significance which he awarded to music. i’ve in the past misidentified those two things as one and the same, but the talent for music is older and more robust than the talent for religion. it is a talent that is exemplary of piety, that is, of our need for devotion, intoxication, catharsis...

—the subtlest challenge for the atheist is how she can express the importance of a cultural migration away from religion that does not contradict our instincts of a secular piety (or as described in the peterson-harris debates: not throwing the baby out with the bath water)—ugh, these ghastly idioms are in need of an update. secular piety?—that is my working description of that hands-clasped posture of devotion one sees at a really good concert—and that is the presupposition of a Bon Iver concert.—

another of the subtlest challenge of new atheism is what to do with its herd instinct in the meantime. while we’re waiting for the rest of the world to take up the courage for truth—a process which both cannot be rushed and is as well overdue—what are we to make of our bad conscience in regards to the herd instinct? for much of the human story there has been no surer way to cultivate a bad conscience in regards to the herd instinct than to have truth on your side. and, without question, we have this bad conscience. in fact it takes the sage intelligence of a sam harris, the darting wit of a christopher hitchens, or the scrupulous and stuttering keenness of a richard dawkins to stand toe-to-toe with the mega-complex of psychological obfuscation which religion is (and which peterson has attached himself like plankton, for the sake of his career as a ‘public intellectual’).

thankfully—that is, gratitude pours forth continuously—there are consolations in the meantime. there are supreme aesthetic revelations which we and everyone else, without exception, can enjoy without celebrating superstition or wallowing in that aforementioned bad conscience. there are transcendental secular experiences, known altogether as art, that can feed, caress, cajole, entrance, intoxicate the deep needing of our inescapable pieties. music is the supreme secular art. in it we can exercise that instinct for devotion that is, even in relation to the oldest religion, ancient.

what i describe as bad conscience (a first rate Nietzschean term) is a corrosive cancer on the human psyche. to cling to truth when the overwhelming majority of your fellow humans have resigned their courage to the magnificent colours of the emperor’s new clothes—is to continuously doubt your own seriousness. it is, as well, a slow journey to the end of the night. there are good reasons to lack courage: for an organism so dependent on each other, one risks being the only one with courage. and despite whatever mock-heroic stance we might strike, there are only a few things are worse for the human animal than being the only one—it is the end of the world.

thankfully. thankfully, there are allegiances in our highest and in our lowest capacities. and of those high allegiances, the ones founds in music enjoy the most depth and breadth. that is the specialty of the musical experience. for those who have traveled too far into their own private little night, music is one of the most profound ways back into the people. and as louis-ferdinand céline already said above, nothing matters in human life if it is not among the people.

there are a thousand little ways towards a spiritus mundi, a global union. the music we make for each other, that fetch tears too deep for words, can be found on each of those thousand ways—

On the origin of religions.— The distinctive invention of the founders of religion is, first: to posit a particular kind of life and everyday custom that have the effect of a disciplina voluntatis and at the same time abolish boredom—[...] To become the founder of a religion one must be psychologically infallible in one’s knowledge of a certain average type of souls who have not yet recognized that they belong together. It is he that brings them together. The founding of a religion therefore always becomes a long festival of recognition.—“” Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science—Section 353

—the musician too is a harbinger of a long festival of recognition, an apostle of a disciplina voluntatis (discipline of the will). recognizing that, for example, those who were enchanted by the divine in music, might have been moreso enchanted by the musicality of the divine.

(a bit of good news)———reading watson lyle’s Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art, and enduring his tremendous talent for fabulation reminded me of how much more work i still need to do in order to speak more eloquently about what i find most exciting in the musical experience. at any rate, i’d like to not write things like this:

Eventually it subsides entirely; but just as surely as humanity is declared, and divinity is made impossible, by the presence of the old

Adam in us, so do we find the restlessness of this semiquaver figure recurring after an expression of spiritual ecstasy impressively suggested, by several bars in unison, for the whole time orchestra. “” watson lyle, Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art

It ebbs and flows, like the voice of a conscience, or like materialistic desires, struggling for supremacy over the exaltation of a dawning spiritual serenity. “” watson lyle, Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art

sure. or:

It is as if we gazed upon a profile of the Christ, in bas-relief of snowy marble, standing out, emblematic of truth and hope, from a shimmering base of silver and purple. “” watson lyle, Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art

i guess so…

anyways, gratitude pours forth….because the most expected has happened, exactly the opportunity i needed has come my way. this whole week i’ve been riding the high of finding out that i’ve been selected as one of the eight participants in a joint writing program by the canadian opera company, national ballet of canada and toronto symphony orchestra. called the Emerging Art Critic mentorship program. we’ll be coached by industry professionals to write a review for a performance for Opera Canada, The Dance Current and Wholenote magazines.

i’m awashed in anxiety and excitement regarding how much i can make of this opportunity—but altogether inconsolably grateful. i’ll need some time to recover from this attack of hope….