(program)

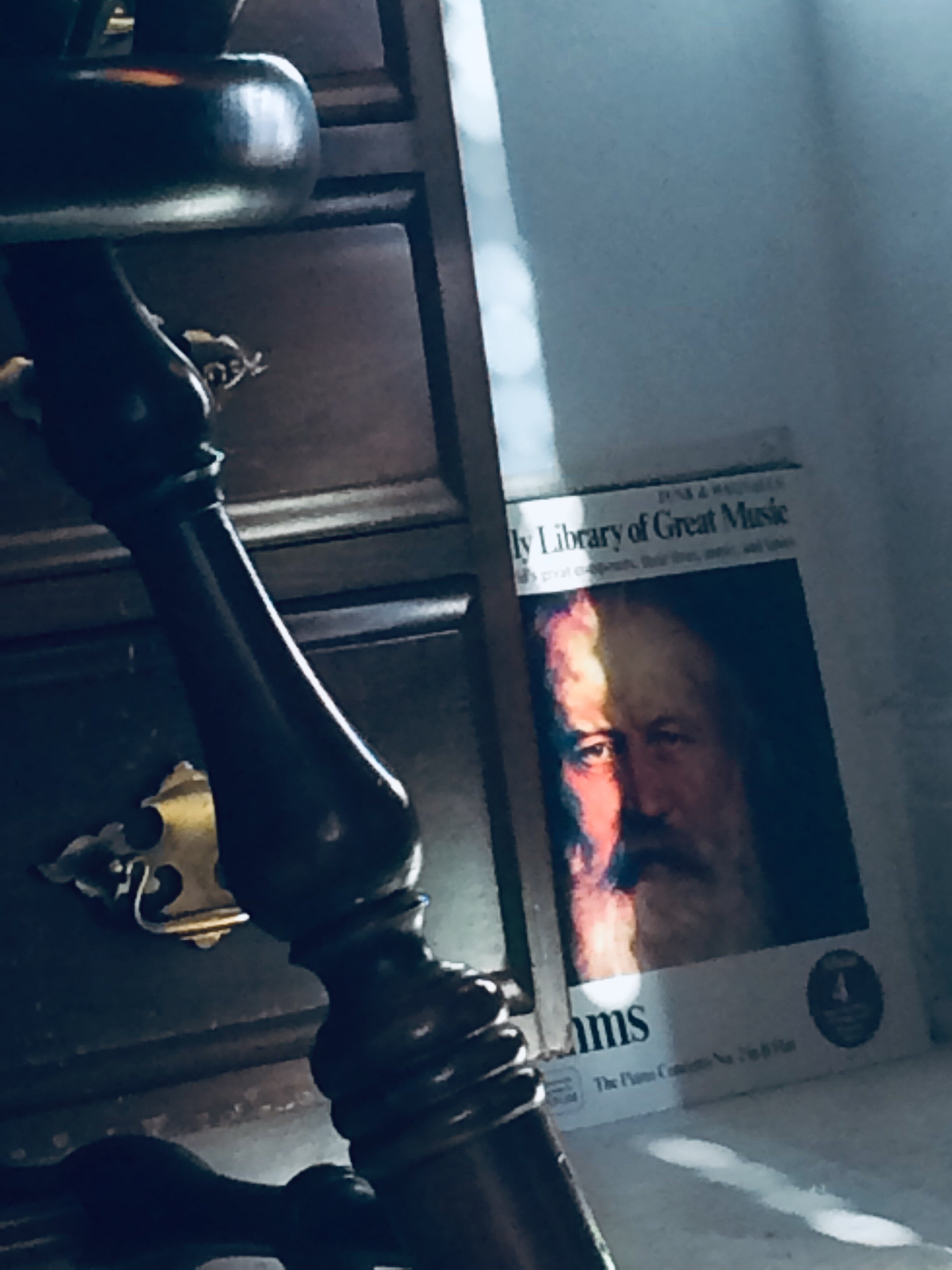

Ace of Diamonds LONDON Recording // Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) // Symphony No.3 in F major, Op.90 // Rafael Kubelik conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Allegro con brio

Andante

Poco allegretto

Allegro

The undersigned...regards the productions of the leaders and pupils of the so-called New German School...as contrary to the innermost spirit of music, strongly to be deplored and condemned. “” extract from the manifesto drafted by johannes brahms and joseph joachim, 1860

Schumann, Chopin, Berlioz and Liszt, the leaders of the post-Beethoven revolutionary movement in music ...seem to have left no impression upon our symphonist. He was either blind or feigned blindness as the eyes of an astonished mankind opened wide and overflowed with tears in the glare of Wagner’s radiant genius...But this man, who has written three symphonies, and probably intends to follow them with another six, can remain unmoved and untouched by such a phenomenon! He is only a leftover of old remains, not a living creature in the mainstream of time. “” extract from hugo wolf’s review of brahms’s first three symphonies, 1884

there’s in biology a word to describe the tendency of a species to revert to ancient/ancestral traits that have perhaps skipped several generations---atavism---and can be used, admittedly by a stretch of the definition, to describe a persistent trait that occasionally rears its head in individual artists and collectives. perhaps in response to hugo wolf’s quote above---a typical wagner stan---it’s aproppo to point out that for the sake of taste, at least in music, a small amount of that kind of deafness is advantageous, necessary even. otherwise the latest, shiniest, wagneriest object might accidentally become lodged in one’s ear: a harbinger of a more complete kind of deafness, unable to hear and be affected by anything not still hot from its very recent happening. wolf’s accusation, which is for brahms really a compliment, is to the effect that brahms is an atavist of the beethovenian style of the symphony---indeed this Symphony No.3 does at instances procure flashbacks to the Pastoral Symphony. but the comparison to beethoven is far from accurate, reactionary, inasmuch as brahms’s musical signature is Classical in font and Romantic in size; to one an extent formulaic and to another individual.

the september stretch of this journal began with a pair of Baroque pieces (week5 and week6)and wraps up here with clara schumann (week8) and brahms, two Romantic composers from practically the same household. i’m still only peripherally familiar with the reality of their relationship---few of the details i’ve encountered rise above speculation---but for the sake of the steadfastness to which the two were committed to each other for most of their adulthood, pairing the two feels more intuitive than pairing clara and her husband...

Although Clara was thirteen years older than Brahms, they might very well have married. But, for reasons that are not clear, their relationship cooled, and they went their separate ways. Their friendship, despite occasional quarrels and hurt feelings on both sides, was a rock for both of them over the years. They each remained single for the rest of their lives. The ‘shy-seeming’ Brahms matured into a bluff old (or old-seeming) bachelor, hiding his feelings beneath a crusty, bearded exterior and often clumsily offending his friends. “” robert philip, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music

Donald Runnicles conducting the Toronto Symphony Orchestra — Courtesy of Toronto Symphony Orchestra and Jag Gundu

the TSO performed this symphony just last week, and it was apparent listening to it again this week just how much i missed the first time around, new notes seemingly coming out of the woodworks. as pointed out by musicologist robert philip (whose Companion to Orchestral Music has been a boon for the occasional sense that’s made in this journal) the sprawling scenery of this symphony unfolds along two main roads: a three-note leaping motif and that recurs throughout the symphony, and a repetitive melody that is launched on woodwinds, tossed around the orchestra, to land in the violin section.

the first movement begins with that three-note motif on woodwinds via a chord progression by 3rds and then by 6th notes. this leads directly into the movement’s main theme on violins, the volume raised to a triumphant incline. the second theme finds voice initially on principal clarinet, thereon passed to cellos, violas and finally picked up in the violin section. that leaping motif is returned to woodwinds at the top of a coda that builds up to a climax and concludes with a sombre reference to the opening bars.

caught Brahms creepin’

Brahms, like Schumann, loved rhythmic confusions and surprises, and this movement is full of them, giving it a particular internal energy. In contrast to this energetic verve, the second main theme is a calm melody on the clarinet. But this is not straightforward either. It curls round, reiterating whole phrases and smaller groups of notes, like someone trying to find the right words. “” robert philip on the first movement, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music

the slow movement, Andante, begins as well with that same transition of a melody from clarinet to violins, a recall of the second theme played on that instrument in the previous movement. as usual, its taken up by cellos and then violins, but this time closes in woodwinds. the third movement begins instead on cellos crafting a derivative of the aforementioned second theme on from the Allegro con brio, another instance of the many duets between the clarinets and cellos in this symphony. thereafter that leaping motif is taken for another spin before the movement finds a small stretch of quiet and the opening melody is reprised on french horns, oboe, then finally on violins.

the fourth movement, lagging slightly behind the pace of the first movement, is just as lively, though much of it is in a minor key:

The finale begins quietly, with a darkly wandering theme on strings and bassoons. This is followed by the sombre chorale from the middle of the slow movement, and then the whole orchestra bursts in with a leaping motif, now given an aggressive edge with sharp dotted rhythms. This calms down to a beautiful, surging theme on cellos and horns, which is closely related to the main theme from the third movement. A great battle rhythm develops, battling until a brief quiet occurs. “” robert philip on the fourth movement, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music

(song of the week: There’s A Man Going ‘Round - jessye norman)

what an exceptional name he’s taken...the first i heard of jessye norman was via british director terence davies, whose films share a consistent belief in the soundtrack not as something conveniently in the background, but an active and suspended moment in the lives of the characters in his films, who trade dialogue for song in the cloistral dimly lit bars of his childhood. “In memory, everything happens to music”---the tagline for one of my favourite of his films, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988). there’s a lot of stillness in that film, at times the characters interrupt a conversation to pose for an imaginary photographer. it was in one of those still moments, after the passing of a particularly domineering father, that i first heard norman’s voice. the father’s death was a relief to his family, as if a black boot---under which they toiled and suffered in silence---had been lifted. hardly a tear was shed, his funeral was a stern and mechanical procession...yet it’s someone’s father that died, however horrible he was, someone to some extent had something to mourn. right in the moment when relief was palpable on screen that norman’s voice, strong and supple, clear and obstinate, a sail cutting high and wide, rises to sing that wrencing elegy on loss:

There's a man going 'round taking names

There's a man going 'round taking names

He's been taking my father's name

An' he left my heart in vain

There's a man going 'round taking names

“” original by Leadbelly

when news of norman’s death, at the age of 74, broke on monday, those were the words that went ringing through my head. since watching Distant Voices five years ago, i’ve come to discover her over and over as an elite soprano, a trailblazer making a name for herself in an arena that lacked much opportunity for visible minorities---but also a diva in the best sense possible, a woman in love with the stage and a voice to maintain that relationship for the better part of the last half century.