Oui, by the love of my skin, I shit on your nose, so it runs down your chin. I kiss your hands, your face, your knees, and your --------, that is, whatever you let me kiss “” mozart in a letter to his cousin maria anna

it was two months ago that i watched fellini’s Casanova, and i’ve been under its spell since; doubtless fellini took liberties in the embellishment of the title character’s excesses and erotic conquests, but the prime subject of the slack-jawed awe at that wild romp of a film were the morbid sensibilities of the 18th century venice that it so faithfully and grotesquely displayed. it was in this same humid and tepid air that wolfgang amadeus came of age as a composer, finding his fame right about the time that giacomo casanova’s legend was established as a household name. mozart arrived in venice in his twenties, ripe and ready for the cult of beauty and terrifying sensuality that city could barely contain.

He was a constant fidget, drumming his fingers, tapping his feet. His favored recreations were all physical: in Salzburg, air rifle competitions and the bowling game skittle; in Vienna, horseback riding and billiards at home. Constanze said he loved dancing, if anything, even more than music. Mozart was small and pale, often ill, nothing much to look at, but he possessed the tireless energy that also marks his music, along with the vibrant sense of drama and comedy and human psychology on display in his opera. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

i’ve been reading excerpts from some his letters to spouses and family and it is to no shock do i discover how easily filth and muck comes to the same composer whose Rondeaus and pretty prestos have made him the poster wunderkind of jolly pastorality. It’s a simple rule i follow: if you’re going to be vulgar, be only as vulgar as you are eloquent, entertain only as much ugliness as your capacity for beauty...

I’ll be sleeping with my dear little wife;---Spruce up your sweet little nest because my little rascal here really deserves it, he has been very well behaved but now he’s itching to possess your sweet … [scratched out]“” mozart in a letter to his wife, constanze

oh yes, the violin concertos: these two works are, in their own way, a nudge in the direction of practising what i referred to the last time around as a gymnastics of attention. i want to believe that this journal has improved those gymnastic capabilities. at one time or another i’ll find myself entirely committed to a certain velocity of being over and instead of all others: either going at the pace of a slow slow tune, or chasing at the heel of some whirling, careening thing, faire le quatre cent coups, etc... perhaps it’s not a particular velocity of being that matters, but the ability--consequent of cultivation and habit--to accelerate between fast and slow without dissolving entirely into either. by way of a small leap of relevance, these concertos are, with their fast-slow-fast structure, are the perfect metaphor.

when should we go wisely and slow? mild and moderate? when should we turn our mind to that realization that however fast we’re travelling, the river is always travelling faster? and when instead should we hurry in the opposition direction and pick up the tempo a little? perhaps what matters most is possessing that agility of spirit that allows one to accelerate between velocities without prejudice towards any one pace.

Mozart was a man of the theatre and had the temperament of an actor, who feigns for a living, who leaps nimbly from one emotion to another and in that can move us to the core. Mozart was a fierce craftsman, he studied and grew throughout his life, and he thought carefully about what he did. But what came out still flowed from a man who was made of music. He spoke sometimes in lace, sometimes from behind mask, but all the same his spirit and soul and his joy and sorrow and love and lust emerged in sound: all at one, he was himself Papageno and Sarastro and Pamina and Tamino. “” jan swafford, Language of the Spirit

the Violin Concerto No.1 is a fairly brief affair with the solo instrument mostly in opposition to the orchestra. the first and second movements both close with extended and unaccompanied cadenzas. in the closing Presto, the violin strikes a more cordial tone with the development of a call-and-response with orchestra. the second violin concerto, written just two years after first--by the 19-year-old composer!--is much more interesting and more recognizable. it relies more on melody, beginning the first movement with the main subject by the orchestra and then taken up by the solo instrument. the middle section of the first violin concerto has been sped up a bit (Andante)and wrapped with more lush and lyricism--reminiscent of the slow movement of his Piano Concerto No.11. the last movement, too, develops in a call-and-response style with mozart’s unique take on the rondo.

(program)

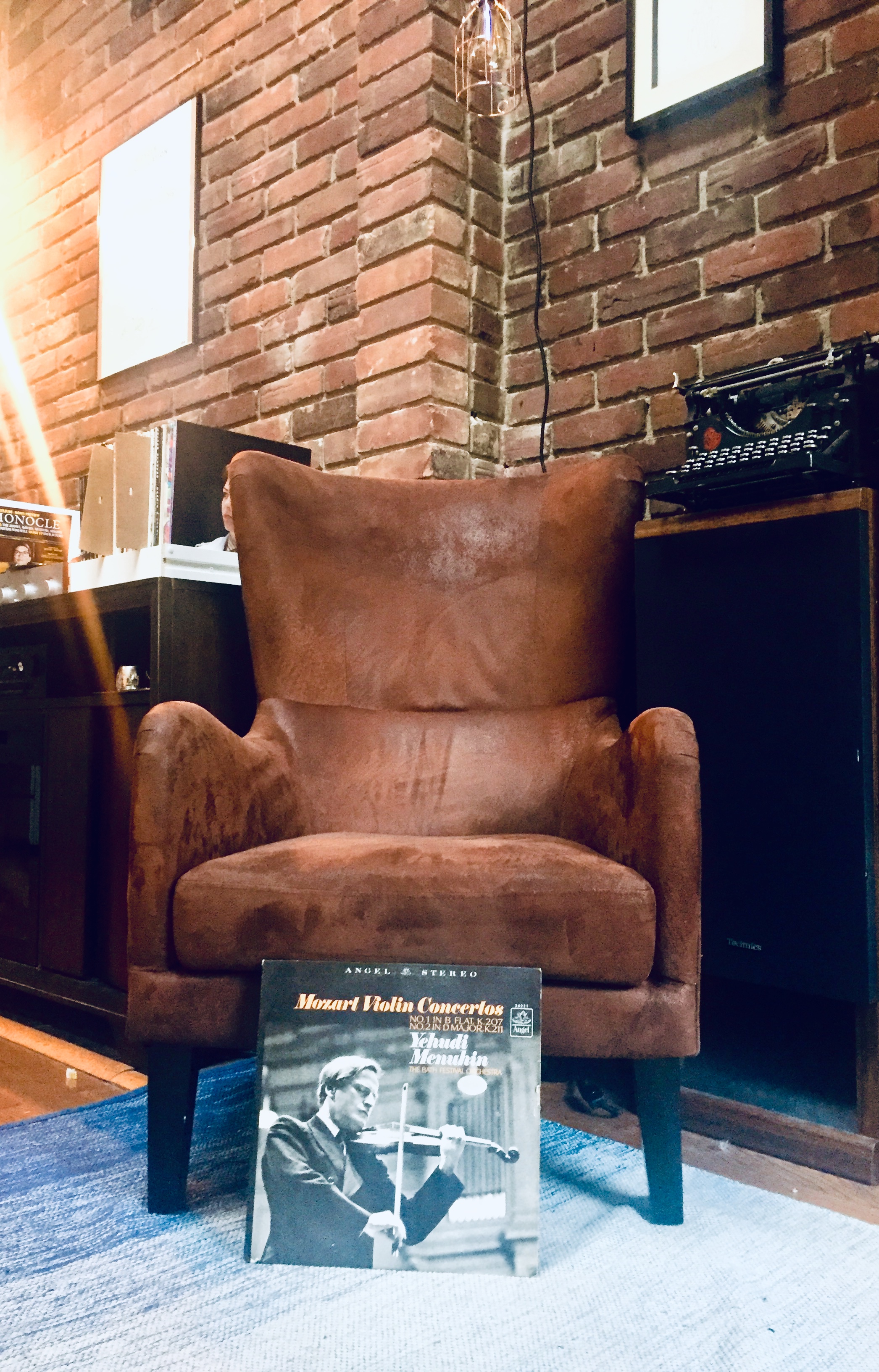

Deutsche Grammophon Recording // Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) // Violin Concerto No.1, in B Flat, K.207; No.2, D Major, K.211

The Bath Festival Orchestra with soloist Yehudi Menuhin

Violin Concerto No.1

Allegro moderato (moderately brisk)

Adagio (slow)

Presto (fast)

Violin Concerto No.2

Allegro moderato

Andante (moderately slow)

Rondeau, Allegro

I must ask you, dearest dunce, why not?---If you happen to be writing … to send my regards to the two Misses Freysinger, why not?--Strange! Why not? And say that I bed the youngest one, Fraulein Josepha, to forgive me, why not?---Why should I not beg her to forgive me? Strange! Why should I not? Say that she must forgive me for having not yet sent her the sonata I promised … Why not?--What?--Why not?--Why should I not send it?--Why not?--Strange “” mozart in a letter to his cousin, maria anna