program)

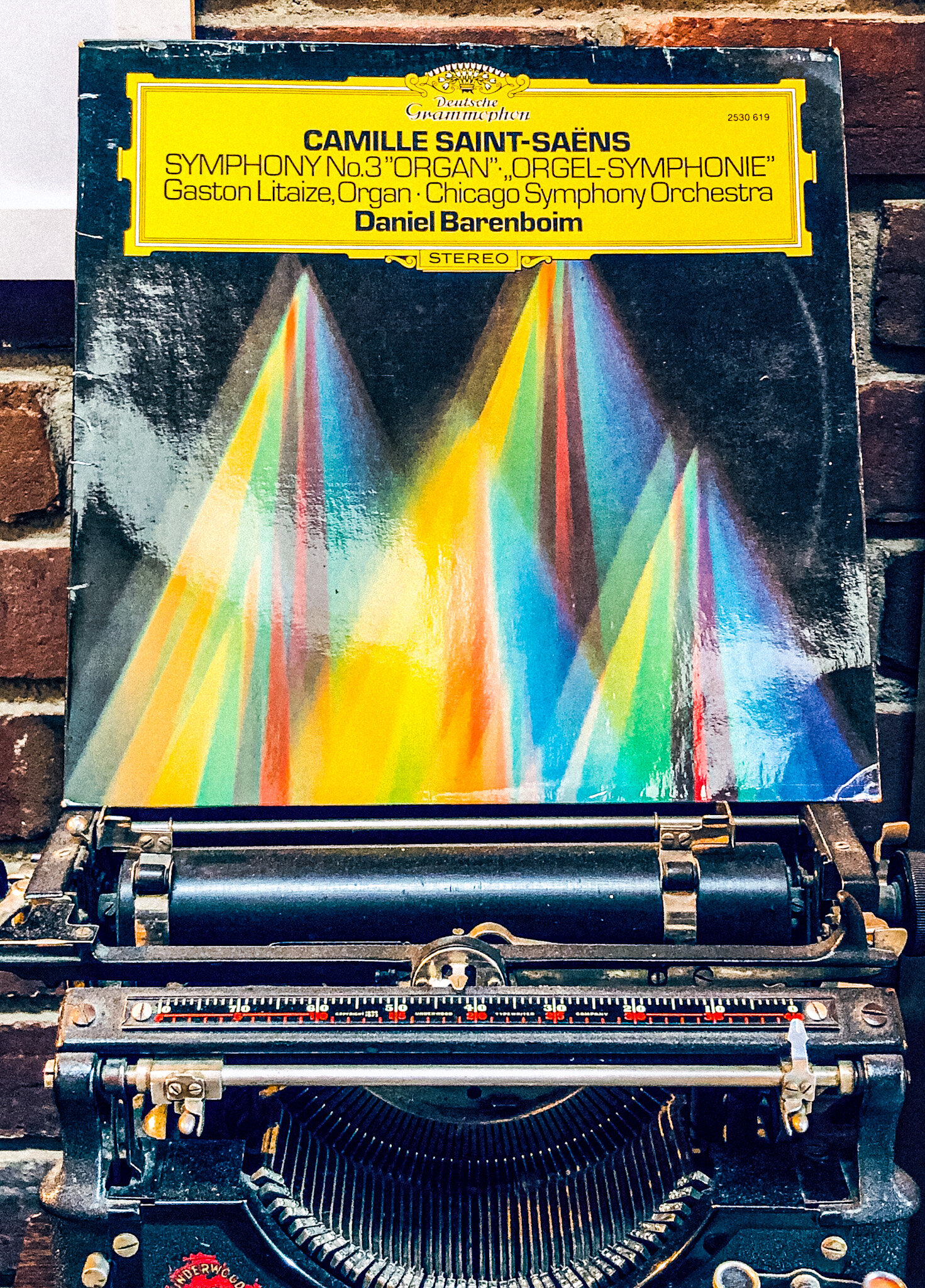

Deutsche Grammophon, printed in Germany

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921)

Symphony No.3 in C Minor, Op.78 “Organ”

The Camarata Contemporary Chamber Orchestra

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Daniel Barenboim.

Gaston Litaize on organ

Symphony No.3

1) Adagio—Allegro moderato—Poco adagio

2) Allegro moderato—Presto—Allegro moderato—Maestoso—Allegro

Into daylight once again I am escaping

Once again goodbye

To symphonies and dirty trees

With parks and plastic clothes

The ghostly garden grows

“” Nathan La Franeer — Joni Mitchell

Compared with the restless and troubled art of today, his music strikes us by its calm, its tranquil harmonies, its velvety modulations, its crystal clearness, its smooth and flowing style, and an elegance that cannot be put into words. Even his classic coldness does us good by its reaction against the exaggerations, sincere as they are, of the new school. At times one feels oneself carried back to Mendelssohn, even to Spontini and the school of Gluck. “” Robert Philip, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion.

i get a little scatter-brained in the middle of july. hence the ramshackle roster of piano compilations and little french songs of the last month on here. nothing a densely packed symphony, inserted in just the right week, can’t fix. Saint-Saëns wrote five symphonies in total, but only published the first three (where are the other two?), the last of which is the most famous of the trio and was dedicated to Liszt who died three months after it’s premiere.

He had very wide musical sympathies. He revived the music of J.S. Bach and Handel, and French composers such as Rameau, Lully, and Charperntier, while at the same time promoting the work of living composers. During a long life he wrote huge quantities of music, including twelve operas. “” Robert Philip on Saint-Saëns, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion.

i don’t know why Saint-Saëns symphonies don’t get the light of day they deserve in the ususal run of the orchestral mill. if there’s one symphony you send to someone trying to find an introduction to the genre, his No.3 is it. so seamlessly it blends the old and emerging, classical and modern sounds, and all throughout is as tightly woven as a Beethoven quartet. indeed fellow French composer Charles Gounod was in the audience at its premiere and seeing the exiting Saint-Saëns exclaimed: There goes the French Beethoven!

Much of Saint-Saëns’s isolation arose from his opposition to the ‘Wagner-mania,’ which had engulfed the musical life of Paris like an epidemic. Saint-Saëns wrote, ‘People who are unable to play the simplest thing on the piano, and who don’t know a word of German, spend whole evenings deciphering the most difficult scores in the world… Wagner was the inventor of everything; there was no music before him and there can be none after’. Although Saint-Saēns admired much of Wagner’s music, he regretted that he found himself surrounded by a generation of young composers for whom Wagner had made the old classical values of Mozart and Beethoven irrelevant. “” Robert Philip, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion.

on paper, the structure is unusual—two long movements instead of the classical four-movement, fast-slow-scherzo-fast format—but listening to it, the progression of the tempos are pretty close to standard. this is my third time coming back to this recording in the last four years, this time around my ears a bit better tuned for parsing symphonic textures—i could barely make out the organ the first time i heard it. there’s more that it seems i’m hearing for the first time than the parts i’m familiar with. of the latter, the Scherzo at the top of the second long movement is, perhaps with the exception of the Scherzo of Dvorak’s 9th Symphony, which premiered less than a decade after this one, the most addictive and melodic Scherzo in this catalogue.

In some ways, the work is influenced by Liszt’s symphonic poems, with their restless passions, grandeur of conception, and exultant episodes. Every trick of the trade is used by Saint-Saëns to pile up an exciting climax towards the end, producing a grandiose effect. In some ways it is an unusual work for a composer more renowned for his wit than for highly charged emotional expression. “” Meirion Bowen, notes for the recording

almost every theme in this symphony is whistle-able, and it’s this melodic character—as subtly infused as the organ (safe for than one deafening instance at the beginning of the second Allegro that it blares at full mast for no reason)—is what makes returning to the symphony a good idea year after year, and why one of our local orchestras should stick it on a program as soon as business reopens again.

(song of the week: ‘Nathan La Franeer’ — Joni Mitchell)

few songs i know describes what it feels like to live in a city as well as the fifth song off of Joni Mitchell’s self-titled 1968 album (though, in fact, the album’s name was Song to a Seagull, but a printing error on the LP cut out parts of that title—spelt out by a flock of birds—leaving only the artist’s name in tact). legend has it that the album’s producer, David Crosby, had Mitchell sing into a grand piano to have her voice reverberate off the strings for more acoustic resonance, to create that ‘full and hollow’ high and lonesome sound unique to her. ‘Nathan La Franeer’ begins with a string phrase identical to my favourite Joni Mitchell song, ‘Cactus Tree’ (also from this album), which describes the free-wheeling ways of a way-faring woman who draws devotion from every face she meets, all of who are tempted to “ask her for eternity”. perhaps it’s her that asks Nathan for a ride earlier in the album:

I hired a coach to take me from confusion to the plane

And though we shared a common space I know I'll never meet again

The driver with his eyebrows furrowed in the rear-view mirror

I read his name and it was plainly written Nathan La Franeer

there’s something in the song that draws out a bit of existential dread: perhaps it’s how she describes a disgruntled cab-driver in a way that sympathizes with him. as if saying that if you spent as much time as he did in the ‘confusion’, you too would have no option but to ‘grumble at the grey’. the disorienting relativism of a metropolis is understood here as the mere dichotomy of two interacting perspectives, both the victim, both the aggressor (if one is to look at life from ‘both sides now’ as goes another Mitchell song). the buyers and the sellers; burglar bells and wishing wells; gangs and girly shows; aging cripples and superman balloons; symphonies and dirty trees; meter maids and street parades—all mixed together, neither up nor down. a bedlam of competing aesthetics which, viewed from a distance, some distant plane, might indeed look something like a ghostly garden.

Throwback to: Year 1 Week49, Year 2 Week49

Click here for the full 2019/2020 roster of composers