Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

24 Preludes , Op.28

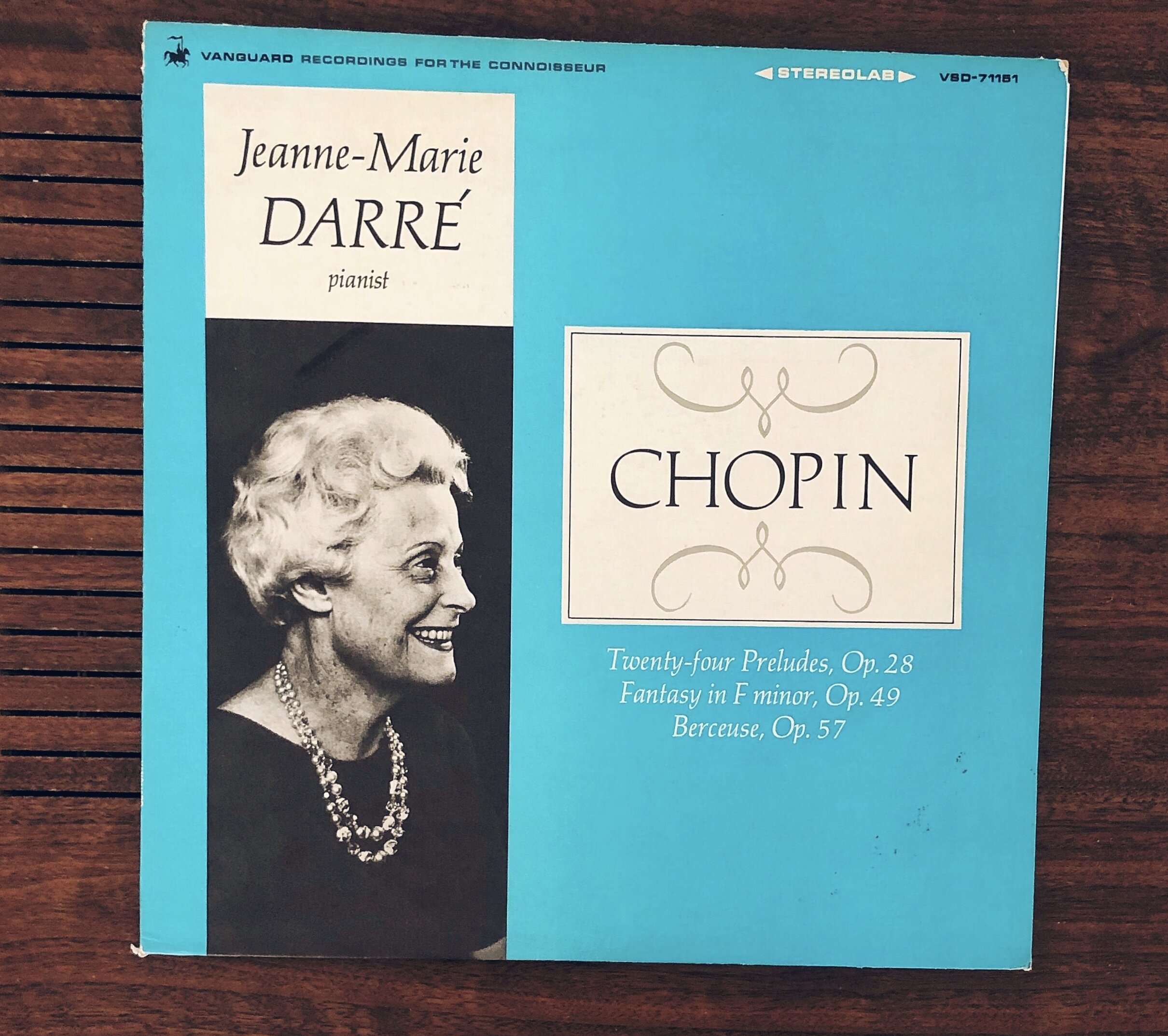

Piano —Jeanne-Marie Darré

Vanguard Recording. Printed in the U.S.A.

Hold on, hold on, my brother

My sister, hold on tight

I finally got my orders

I’ll be marching through the morning

Marching through the night

Moving cross the borders

Of my secret life

“—” In My Secret Life - Leonard Cohen

He was a snob and a social butterfly to whom moving in the best circles meant much. He was fastidious in his toilet and dressed in the height of fashion, even foppishly so; kept a carriage and a valet; had a precise mind and precise manners; could be witty, was a fine mimic and had a sharp, malicious tongue; was ultra conservative in his tastes.

He made a good deal of money and spent it lavishly, always complaining that he did not have more.[…] Good taste meant very much to him. It meant more to him than the romantic movement that was sweeping Europe; he avoided that as much as he could. Delacroix was perhaps his closest friend, but he did not understand, or even like, the paintings of Delacroix. He was not particularly well read. He was on good terms with all of the musicians of his day but did not like their music. He abhorred the scores of Berlioz; considered Liszt’s music empty; told his friend Stephen Heller that Schumann’s Carnival was not music at all; ignored the work of Mendelssohn. He had no interest in Schubert, and Beethoven disturbed him […] The only two composers who apparently meant anything to him were Bach and Mozart. Those he adored. He was a romantic who hated romanticism. “—” Harold C. Schonberg

To get a better sense of Chopin’s fame in it’s nascent years, I’ve been reading Alan Walker’s Fryderyk Chopin—a 700-page tome about the composer’s mere 39 years of life—and came across the first impressions he made on contemporary music critic Heinrich Heine. A bad review is a bit like a trench that you dig yourself into in hopes of being able to get out of it with a good review in the future, Heine was renowned for the former and seldom dispersed the latter. This the same critic who once praised a writer for being “a young man with a great future behind him,” (the poor victim being Alfred de Musset, one time lover to Chopin’s long-time lover George Sand). So to be showered with compliments by such a wickedly forked tongue meant a bit more than the sparkling compliments—perhaps over the muffle of powdered kerchiefs in dimly lit parlours—regarding Chopin’s power on his instrument.

Chopin had been born in a vanquished nation that was writhing under the heel of mighty and covetous neighbours. His mother, fiercely Polish, was lady-in-writing to a countess. His father, an egalitarian from Lorraine, was an erstwhile snuff salesman and sometime flute teacher whose urbane ways endeared him to the nobility. Their son was to be forever torn between the environmental polarities to which he was heir — social graces and social justice. “—” Notes from the recording / James Lyons

A romantic who hated romanticism—we tend to gloss over Chopin’s aristocratic leaning, yet it’s right there, in his hands: the steady, at the times cold, arithmetic detachment in the bass; then there’s the mercurially tempered treble: fire and brimstone (Prelude No.18 in F minor) in tandem with lapis lazuli (Prelude No.15 in D-flat major).

What distinguished Chopin from the acrobats was his lack of interest in technique as an end in itself—a saving grace that he might never have possessed if he, too, had endured a formal piano education. He belonged to no school, he subscribed to no dogma. Everything he knew about piano playing he had discovered for himself. “—” Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times / Alan Walker

Chopin wasn’t exactly the freewheeling diy-swashbuckler that the many variations of the above quote suggests. He fussed over technique as much as the academics of the pianoforte of his day. His distinguishing feature being that he didn’t rely solely on the accolades of technique, technique could always be found prostrated at the foot of the moods and atmosphere of his compositions. And where he cared most about technique was in the manner in which the piano could be made to sing:

He recommended a flat finger for a singing touch; he employed the organist’s favorite device of finger substitution to sustain melodic lines; and he favoured a low piano stool, finding it more comfortable than the high one adopted by the hard-hitting virtuosos who liked to descend on everything from a great height. “—” Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times / Alan Walker

My favourite of these Preludes?—it’s hard to choose. Played in this recording by pianist Jeanne-Marie Darré, the 24 Preludes run for an average length of 88 seconds, there’s barely enough to sink one’s teeth into, they waft along as ephemerally as a memory instigated by scent. Though they do pair well with with the frantic energy of mid-August, a counterpoint to desperate attempts at making the most of what’s left summer and so on. Actually it’s one of the appendages of this record, Berceuse (Op.57), tagged on at the end to fill space, that’s the runaway favourite for me. It’s an almost perfect specimen of the dichotomy of the composer as an aesthetically conservative yet impassioned, but reluctant, romantic. It’s a crystalline distillation of the naked and unadorned sincerity that I’ve found Chopin’s music frequently ascends to.

When he plays I forget all other masters of the instrument, or mere skill, and sink into the sweet abyss of his music, into the melancholy rapture of his exquisite and profound creations. Chopin is the great and genial poet of sweet sound, who should only be named with Mozart, or Beethoven, or Rossini. “—” Heinrich Heine

SONG OF THE WEEK: ‘In My Secret Life’ — Leonard Cohen

Sincere—that was the compliment from a friend this week, regarding this journal. I don’t always manage it on here, but it’s a good reminder of why I started this, and what matters most in any kind of writing. Especially writing about music—so much bullshit gets through the door—it’s easy to forget how perfectly enough it is to say that a piece of music made you feel good.

That said…It’s an obscene number of jobs that I’ve had in the last decade. Though I think I can forgive even the worst of them on account of the handful of good songs I managed to reap from the rambling molten-pink cloud of corporate-approved playlists hovering just above my head at each one of these soul-sucking enterprises. Try and try as I may—and I did—I was only able to pull just two such germs from my time at Monocle Magazine—perfectly decent people and, if you’re loaded, a decent magazine. Though the 24-hour ‘Monocle Radio’ did some serious damage to morale, it did provide me with an unexpected rendezvous with only the second song that I know from the only Flight Facilities album that I know of (‘Crave You’ is an eternal banger, no debate). The second was an overly jazzed-up cover of this Leonard Cohen song, though I felt right away that the upbeat-urbanite overly-optimistic take didn’t quite fit the mood of the lyrics. There’s a deep blue sea in this song, the bottom of which is scraped Cohen’s deep rumbling unembellished singing—just like the Berceuse, come to think of it. It’s not just the bass of his voice that contrasts starkly with the aforementioned cover, there’s a sincerity to his simplicity—lost in the affectations of the cover—that makes this song feel so damn good.

Throwback to: YR3 WEEK3, YR2 WEEK2

Click here for the full 2020/2021 roster of selected recordings