Author: Caleigh McEachern

As video games and consoles continue to evolve, games have become more complex with more detailed environments, smarter AI and increasingly realistic art and animation. Many AAA games released over the past decade require between 30 and 60 hours to complete, which means players are immersed in a story for as many hours as three to five seasons of a binge-able Netflix series. Stories in video games are not passively consumed: players interact with the world around them and experience the narrative as they progress through the game.

Players also make decisions while in the game world. The nature of the decisions players make can be numerous or more limited but, generally, players can always decide which directions to go, what areas to explore and what they will look at or interact with. Players who would rather play the action sequences of a game can decide to rush through an environment without exploring the space at all. However, games that use environmental storytelling to great effect, such as BioShock Infinite, reward players who take the time to explore all the available spaces. Exploration in BioShock Infinite leads to moments of discovery where the player is then invited to interpret this new information. Discovery is an active process that puts the player’s experience at the forefront of the story’s delivery, as it is the player’s in-game actions that move the story forward. More importantly, it is incredibly satisfying to uncover secrets and hidden areas and gain a greater understanding of how the world works.

BioShock Infinite is a first-person game and the third of the BioShock series, a series that is known for its well-crafted narratives. Before I continue, it should be noted that this analysis may contain spoilers. Video games, by nature, are immersive, and they face the challenge of teaching players how the game works in a way that does not break a player’s immersion. When we begin the game, we, the player, do not know much about ourselves as the inhabitor of the avatar. However, BioShock Infinite uses this to its advantage by following the journey of a character that, like the player, is entering an unknown world so the player’s lack of knowledge about the world around them makes sense within the larger story.

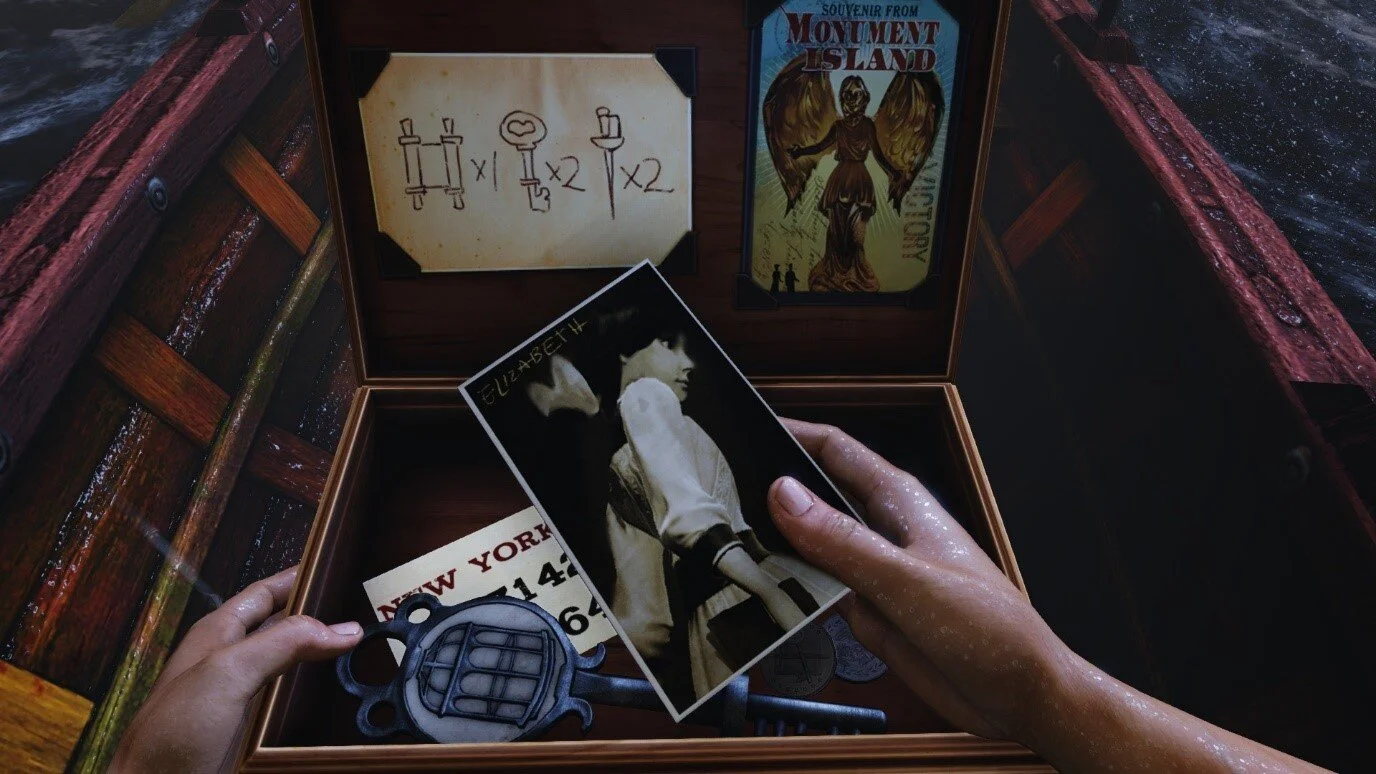

In BioShock Infinite, the year is 1912 and the player is Booker DeWitt, a man who begins the game seated on a rowboat with two strangers, making its way to a lighthouse. He opens the suitcase on his lap, which contains an image of a girl, and a scrawled message on the back with his objective: collect Elizabeth and bring her to New York.

Once DeWitt reaches the top of the lighthouse and enters in the code pictured on a card in the suitcase, he enters a capsule and is rocketed into the atmosphere to the city of Columbia, a steampunk city in the clouds. From the moment the player exits the rocket, they are surrounded with religious imagery of a man named Father Comstock and they must pass through a flooded church and undergo a baptismal ceremony before they may truly enter the city.

The player then enters Columbia and, while they wait for the gate to lower, they can marvel at the pristine white Colonial architecture, beautifully illuminated by the rays of sunlight shining through the clouds. A blimp passes by in the distance. The player may then walk down the perfectly unblemished pathway towards the statue of Father Comstock, listening in on conversations between the citizens as they pass. A couple leaning over the bridge railing remark, “A perfect day for the celebration,” “Father Comstock must have foreseen, and planned it just this way.” A paperboy hawks at the passersby, “A full transcript of Father Comstock’s address to you, the Columbian people, on the holy forgiveness of our dead Lady Comstock, our beloved Mother of Forgiveness!” A woman gazing at the statue tells the man standing with her, “Oh, that statue, I just think it fails to capture Father Comstock’s absolute, oh you know, divinity.” A mother sitting with her young son on a picnic blanket scolds him, “Life does not matter to a Liberty Scout, there’s no room for preference, only duty.” And finally, a young man wraps his arm around the shoulder of another man and says encouragingly to a young woman with them, “Stal’s alright I tell you, he says he’s for faith, family, and fatherland, and who could be against all that?”

Much like readers, players can “read” the environment around them and draw inferences based on what they see and hear. In these 30 seconds of gameplay, the player can interpret a great deal of information from the environment and the conversations between the citizens. The language the citizens speak is consistent with the 1912 setting, but the conversations point to a troubling religious fanaticism and the city’s leader, Father Comstock, appears to be artificially endowed with divinity, like a cultish God. The mother who tells her son that “life does not matter to a Liberty Scout, only duty” echoes the values of obedience, sacrifice, and service to the state that formed the basis of the Hitler’s Youth indoctrination, and the fact that they are enjoying a picnic on a nice day almost masks the unsettling nature of her comment. The young man talking up his friend to their female companion positions his friend Stal’s values of “faith, family, and fatherland”, which again echo the kind of language used in Nazi Germany, as correct values one should hold.

Exploring the streets and shops provides more information about the world’s etiquette, social norms, and values. The player encounters many signs on shops that say “pilgrims welcome,” indicating to the player that Columbia is considered to be a holy city - it is literally in the Heavens. In the same way that a reader would understand the grammatical meaning of a sign that says, “Pilgrim’s Welcome”, the psychological understanding of what such a sign means depends on the context it exists within. Such signage in store windows invites the player to interpret possible explanations: its message is welcoming and implies that Columbia is a place that religious followers journey to. But at this point, the player begins to question the religious atmosphere and notice that there is something unsettling under Columbia’s idyllic surface. If pilgrims are welcome, the unspoken message underneath begs the question, who is not welcome?

The player may also choose to explore the environment and discover and listen to the voxophone recordings and kinetoscope boxes. These supplementary materials provide historical information about the player’s world. The kinetoscope, or moving picture boxes, reveal state-sanctioned propaganda, while the voxophone recordings reveal the personal opinions of citizens. These recordings help to construct the player’s understanding of Columbia as a theocratic dictatorship through two opposing poles, the state’s propagandistic historical record and the lived experience of the citizens. Player’s interpret meaning from the juxtaposition between the state’s version of history and the secret opinions of the citizens and, with every new voxophone discovery, the true nature of the city’s lies, deceits, racism and the atrocious treatment of its minority population are revealed.

The darkness that exists under the surface of the seemingly idyllic Columbia is made overtly apparent to the player fairly early in the game, when the player must take a front seat at a raffle where a young mixed-race couple is displayed on stage, tied up and surrounded with racist imagery.

However, while Columbia’s racism is blatant in the raffle scene, the player also encounters more subtle interaction points that, upon closer inspection, speak to the prejudice and discrimination at the heart of this society. Before the player reaches the raffle, they pass through the fairgrounds where they may play some carnival games and win some money, simultaneously learning how to use the game’s weapons. The carnival game, “Hunt Down the Vox,” depicts the Vox as evil people, shown in the billboard images with weapons, bags over their heads that mask their identities and faces contorted in sinister expressions. The carnival game normalizes and encourages violence against the Vox and demonstrates the state’s view that the Vox are disgusting and must be eradicated. The player at this point in the game has no knowledge of who the Vox are, or why they are “deserving” of being shot down, so they might accept without question that the Vox are the enemy or they might question the state’s view of the Vox, given what they have already interpreted from the game so far.

The game subtly hints at the player to question and distrust the state through the advertisements and billboards the player sees scattered throughout the environment. The advertisements are depicted in the visual style of propaganda posters, imploring its citizens to behave a certain way, using all the stylistic cues of classic propaganda imagery.

Jeremiah Fink, the inventor whose name is plastered on every manufactured object in the city, points to the player in a poster that looks almost identical to the classic “Uncle Sam Wants You” propaganda poster from the Vietnam War era of American history. This poster draws such visual cues to subtly point to the way the state of Columbia operates. But there is also a hidden meaning within this poster that players may only discover as they progress through the game. How did this society come to arrive at this propaganda poster design, when in our version of history, it was not created until many years later? There are many moments where the player learns that the city of Columbia is very technologically advanced for its time, and as they progress, they begin to uncover the reasons why.

Other posters the player encounters use the same visual imagery of Soviet era propaganda, with similar themes of loyalty to the state, duty and the value of work. Players who take the time to look closely at this poster and “read” the visual imagery will notice the domineering white man who points authoritatively forward, directing a line of black silhouettes. The silhouettes are clearly laborers, while the man pointing is dressed in a blue-collared shirt. The use of black silhouettes is a recurring visual image in the game’s posters and, in certain cases, it is obvious that the black silhouettes are a stand in for Black people.

Once the player realizes that black silhouettes are used as a visual device to dehumanize Black people, as only white people are depicted as fully formed humans with faces and expressions, the racist undertones of all the posters’ imagery becomes clearer.

Posters the player finds in the factories of Columbia convey the state’s views about labor and utilize these propaganda posters to intimidate the laborers that work in these buildings. Loyalty to the state, patriotism, and a fear of outsiders are all visually communicated in these posters.

One scene that stands out in BioShock Infinite for presenting players with opportunities to make visual connections and interpret their meaning occurs when the player first arrives in Finkton, the manufacturing sector of Columbia.

This propaganda poster presents a joyful white family, looking boldly into the bright future that awaits them in Finkton. The man is a laborer and the move to Finkton promises work so he can provide for his family. However, the player might notice the disconnect between the brightly coloured propaganda poster with the smiling faces of a white family, and the people they see around them on these docks. At first, the obvious police presence stands out. At no point in the player’s wanderings of the fairgrounds do they come across patrolling guards. But when the player looks around, they find the families around them don’t look like the smiling families in the poster. Gone are the pristine white clothing the player saw on the citizens at the beginning of the game; these families are all wearing laborers clothes that are ripped and torn.

Moreover, this is one of the first times the player sees anyone of a different race existing openly. In Finkton, the racism and exploitation at the heart of Columbian society is further reinforced by the types of architecture, the propaganda posters, the people that inhabit the space and the hidden voxophones that share the thoughts and feelings of the exploited citizens. The juxtaposition between the narrative the state wants its citizens to buy into and the lived experience of the citizens underscores the player’s growing feeling that the state cannot be trusted.

BioShock Infinite also distributes important narrative information through the game world in visual vignettes that the player encounters again and again. Most notably are the characters of the Lutece twins, who appear to the player when they enter the raffle area. The twins ask DeWitt to flip a coin, he calls tails, flips heads, and the woman marks the outcome with chalk on the board.

They both seem unsurprised with the result of the coin toss, and as they turn and walk away, the back of the board is revealed to the player.

There are many ways the player might interpret this information, and it is presented so simply and without further explanation that it is unlikely the player will actually uncover the real meaning behind this interaction until much later in the game. This moment of discovery and interpretation leaves players with more questions than answers at first. Who are these people? Why did they have me flip a coin? Why has the coin only flipped as heads? How long have they been conducting this coin test? Who have they conducted this coin test on? Observant players might draw the connection between the two characters’ voices and mannerisms and realize that the twins are in fact the two strangers rowing the boat at the very beginning of the game. But even that realization only leaves the player with more questions, questions that can only be answered as they continue to explore the space and make special note of every interaction they have with these two characters.

BioShock Infinite uses environmental storytelling to foreshadow and convey important narrative information to the player and, to understand the spatial and visual information, players employ the same methodology of interpretation that readers do when reading texts. By distributing moments of discovery and interpretation across the game’s environment that the player must explore to uncover, be it through hidden areas, the décor and advertisements, the supplementary material of the voxophone recordings and kinetoscope boxes and the recurring vignettes, players are always collecting pieces of the larger puzzle that is the game world and the many mysteries that lie within it. Part of the player’s journey through this game is the discovery of who they are: who is Brooker DeWitt, and what is his relationship to this place.

By deliberately withholding information about that game’s world, BioShock Infinite creates a mysterious narrative about the larger world, and the character the player embodies, that the player uncovers through game play. In this way, it is the player who controls how much information they wish to discover. Players who take the time to explore all the available spaces, listen to conversations, read the signs and collect the hidden supplementary materials gain a much greater understanding of how the world works. The more a player interprets the space, the more layered the narrative becomes, making the player the agent of the storytelling and driving the story forward through their own self-directed, in-game actions. Environmental storytelling creates memorable player experiences and is the hallmark of the spatial and interactive nature of video games as a medium.

It is no wonder that games like BioShock Infinite can hold a player’s attention for the many hours of game play that is required to complete it. It is not only beautiful but it creates a living, breathing world with complexities and mysteries that players want to discover. And take it from me, BioShock Infinite is the kind of game you want to play through a second time to catch all the little details you missed in the first play through.

All images are screenshots of Bioshock Infinite, a video game developed by Irrational Games and published by 2K Games.