My music is not free from dryness, but that’s the price of precision. “” igor stravinsky

he would have said it better had he said: ‘That is the price I have to pay for precision’ ….

the discipline of precision, not for the sake of precision alone but of its service to the cathartic element in music, that is the promise and future of the classical canon’s accumulated repertoire. inasmuch as precision is a prefect to form, its ultimate realization in music is always subordinate to content and lyricism, the entire ‘terrible narcosis’ engendering the spirit of the neoclassical russian composer. ironically, this subordination of form to content, precision to languor, is the spirit and context of stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps.

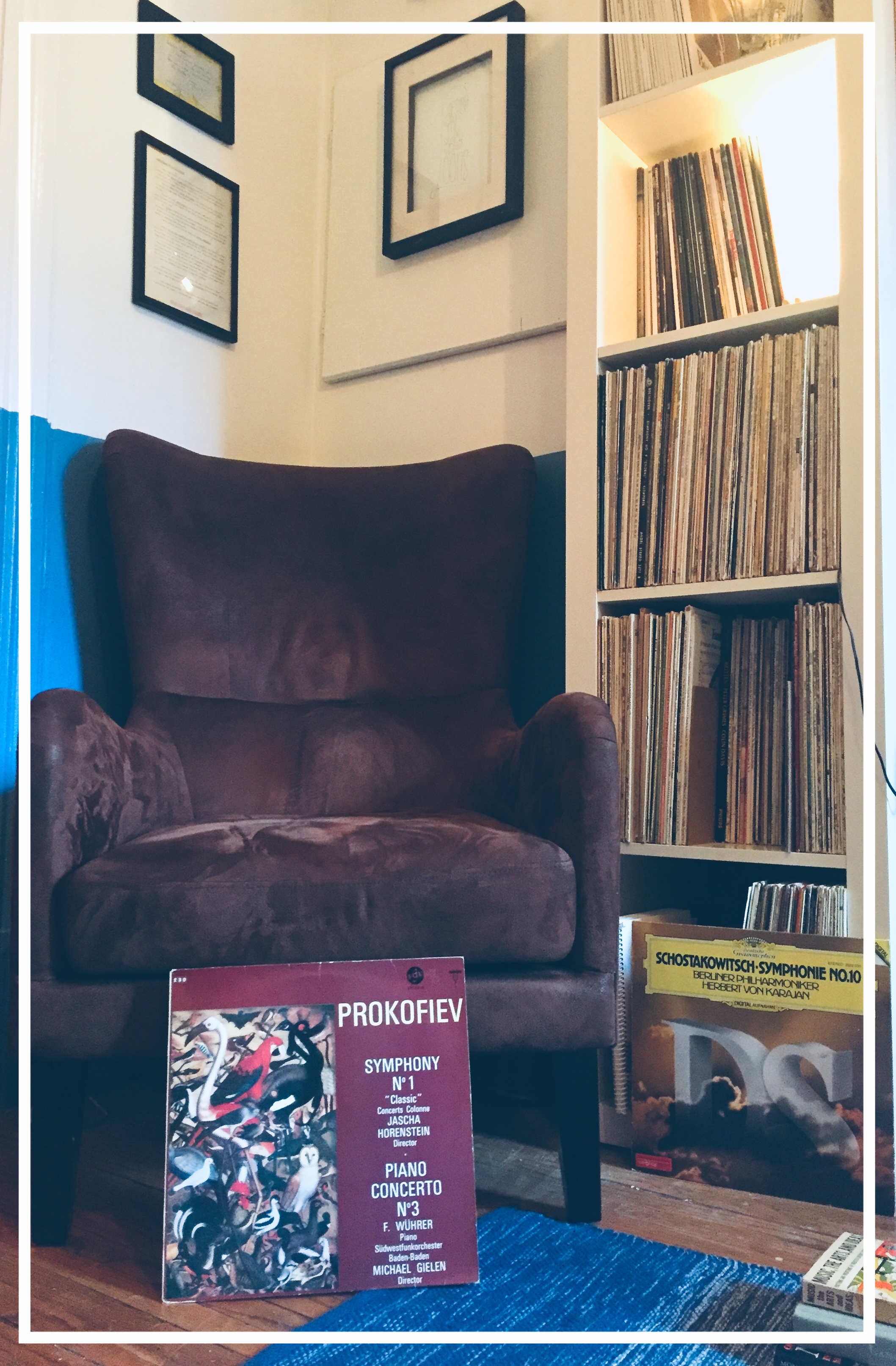

—prokofiev’s first symphony is an example of the codependence of precision and lyricism. it is in comparison a more humid, more mediterranean Sacre. it is characteristic of that same spasmodic jazz-age restlessness of Sacre (all of schoenberg’s ‘emancipation of dissonance’), but its sharp angles are softened in the slightest by a sort of waltzing lilt. and it is altogether more cheerful, sociable, in comparison to the more decidedly awkward manifestations of his contemporary’s experiments:

The Classic Symphony — whatever the initial intention of composer — reflects Prokofiev’s authentic lyrical gift and is the affirmation of the imperishable quality of lyricism in today’s world of dry and primitive styles of music. Perhaps it was necessary to treat the lyricism with ease…Prokofiev never lacked homour, contrary to some of his contemporaries. “” harry halbreich, notes from the recording.

the reference is obviously to stravinsky—and the shade is well thrown. nevertheless, there are few other places more interesting, or more imaginative, than the multivariety of unique identities that populated the first half of the previous century’s russian composers: stravinsky’s dryness, rachmaninoff’s lush lyricism—prokofiev: perhaps a mixing on both? all offshoots of course of that late 19th-century bellwether: pyotr ilyich.

but the comparisons aren’t necessary, these works are unique in their own context: the tremendous volleys of optimism launched by the breathless pistons of the wind section of the first symphony’s fourth movement—and the sprindrifts that are jettisoned from the lofty riffs of the cadenzas of the pianoforte in his third piano concerto.

(program)———

Vox Recording. Printed in the Netherlands // Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) // Symphony No. 1 in D Major, Op. 25 “Classic” / Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 24

Symphony No. 1 in D Major, Op. 25 “Classic”

Allegro

Larghetto

Gavotte (Non troppo allegro)

Finale (Molto vivace)

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 24

Andante

Theme and Variations

Andantino

Allegro ma non troppo

(“Classic”)———

perhaps this is one of those petty things i’d be better off editing out, but: nothing propels me more in the other direction of seriousness in regards to someone’s taste than any talk or reference to an artwork as a ‘Classic’. ugh. it always rings in my ear, regardless of whatever tone is employed, as the clanking of a small chest being dragged up to the attic, stowed away and out of sight, never to be pried open again. that is the presupposition of the “Classic” label—an artwork whose value is undeniable, but cannot be taken seriously as having any significance to ones life simply because it’s not riding the wave of current events, one can only armire it at a distance…and immediately move on from it without penetrating anything more than the most superficial appraisal. is it no longer the case that an artwork is successful partly because its seriousness surpasses the gaze of its immediate audience, and the bubble of the contemporary?

i’m not sure why prokofiev’s first symphony is subtitled “Classic”—but to the first-timing general public, such a moniker makes the symphony more susceptible to be relegated by posterity to a historical realm just beyond seriousness—or perhaps what i really mean is relevance? is it no longer the case that an artistry is expected to surpass—even if beholden to—the contemporary?

perhaps the same misnomer is suffered by the ‘classical’ genre as a whole. what is classical music at first glance except the upkeep of good posture and rigid poses in music?

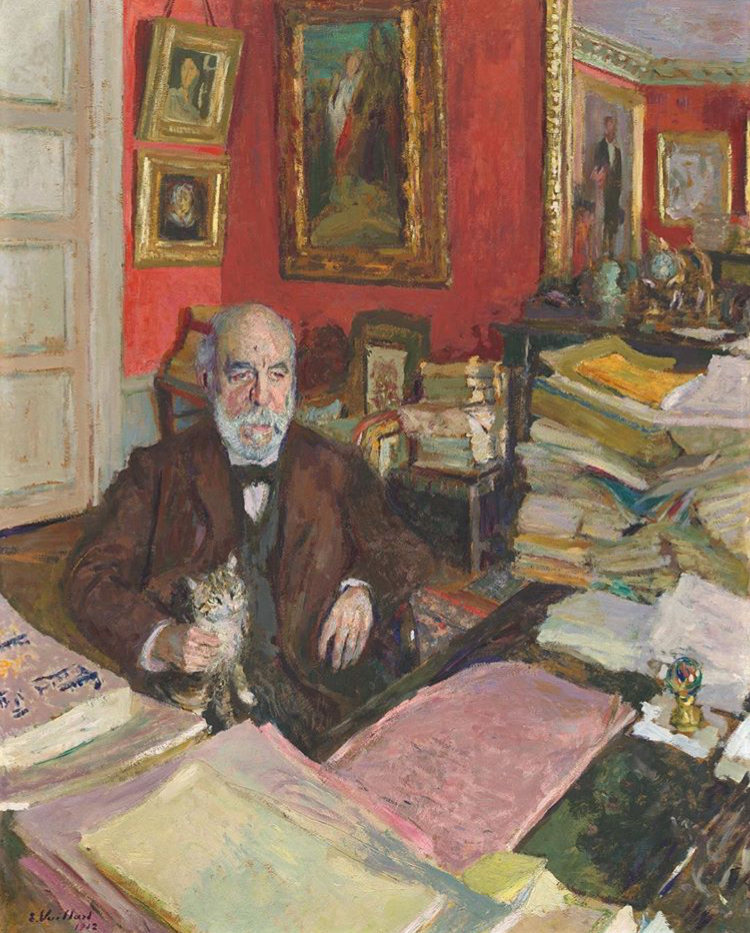

(edouard vuilliard’s Théodore Duret)———

aside from roger ebert, i have very little mental imagery of what resembles an arts critic. what i really mean: is there a definitive aesthetic of the art critic?

théodore duret (1838-1927) was a french art critic and early supporter of manet, and impressionism as a style. perhaps as a thank you for his championship of their aesthetic, several impressionists painted the critic throughout his life, the last of which was courtesy of french painter édouard vuillard. it’s a picturesque snapshot of duret in his apartment, a cozy paper-smothered fort—the result of a lifetime’s refinery of taste, tastelessly scattered about him whilst he stares absentmindedly, inwardly and fidgets with his more attentive feline companion. in summa summarum: it’s a scene of which the subject therein appears socially unavailable…the partially visible door behind him perhaps was at once a revolving door for those artists he spent his life appraising.

no—that’s not the image of the critic i have in mind, whose life’s work is a relic of the past, a wall of ‘classics’, a fortification against the onslaughts of the workaday...

perhaps my interpretation of the painting isn’t exactly accurate? or is it an idealized snapshot of a dandy recluse that belies the adventurous metropolitan japanophile that was a much younger théodore duret?

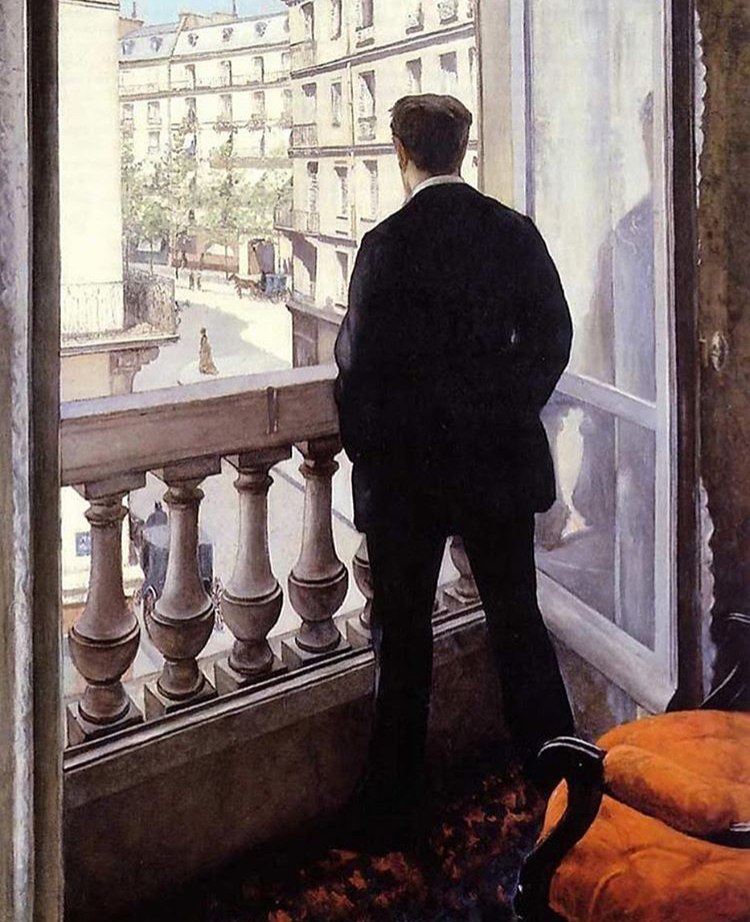

at first (second, third) and every glance since, gustave caillebotte’s painting ‘Jeune homme à sa fenêtre’ (Young Man at his Window) remains the best description of the art critic i can find: athletically vertical, severe in her spectrum of intrigues, a preference for anonymity, for whom every artwork encountered—regardless of its critical merit—begins with a tremendous question mark, a thing to be dragged into her most private corners and feasted upon….

at first (second, third) and every glance since, gustave caillebotte’s painting ‘Jeune homme à sa fenêtre’ (Young Man at his Window) remains the best description of the art critic i can find: athletically vertical, severe in her spectrum of intrigues, a preference for anonymity, for whom every artwork encountered—regardless of its critical merit—begins with a tremendous question mark, a thing to be dragged into her most private corners and feasted upon….

at first (second, third) and every glance since, gustave caillebotte’s painting ‘Jeune homme à sa fenêtre’ (Young Man at his Window) remains the best description of the art critic i can find: athletically vertical, severe in her spectrum of intrigues, a preference for anonymity, for whom every artwork encountered—regardless of its critical merit—begins with a tremendous question mark, a thing to be dragged into her most private corners and feasted upon….

feasted upon?—in his poem ‘Love after Love’ derek walcott poses a tremendous challenge in the simplest unadorned words with which he closes that poem: “Sit. Feast upon your life”—that is the essence of caillebotte’s young man standing at his fenêtre. and that is the essence of the art critic as i imagine it: a feasting fiend gnawing lasciviously at every artistic representation of her tremendous capacity for living. —and that’s the kind of shit you can’t do sitting down.